- Last edited on May 22, 2020

Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT)

Primer

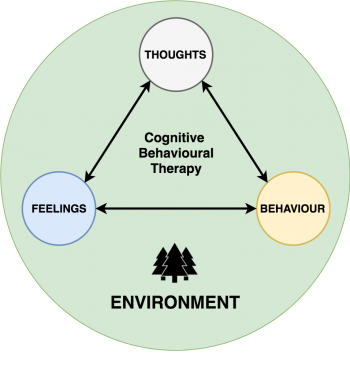

Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) is a structured, time-limited, psychotherapy that identifies and addresses persistent maladaptive thought patterns to change emotions (e.g. - depression/anxiety) and behaviours (anhedonia). It uses strategies such as goal-setting, breathing techniques, visualization, and mindfulness to decrease emotional distress and self-defeating behaviour.

Indications

CBT is used as monotherapy or in combination with medication for major depressive disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, and eating disorders. If a patient has cognitive distortions and avoidance behaviour, this make them a good candidate for CBT.

Format

CBT can be delivered in a wide variety of formats. Group and remote delivery (online or phone) CBT works as well as individual therapy.[1]

Efficacy

CBT provides also provides stronger protection from relapse following treatment discontinuation compared to medications.[2][3] When depression-specific psychotherapies are delivered in routine practice, recovery rates from depression are close to 50%.[4]

Techniques

Treatment is generally time-limited (approximately 12 sessions). Cognitive techniques include identifying distortions such as overgeneralization of negative events, catastrophizing, minimizing positive events, and maximizing negative events. Patients work with therapists to identify and change cognitive distortions and avoidance behaviours that cause their symptoms. This frequently involves keeping diaries or “thought records” outside of sessions and practicing behavioural strategies learned in sessions.

Principles

- CBT is based on an ever-evolving formulation of patients’ problems and an individual conceptualization of each patient in cognitive terms.

- CBT requires a good therapeutic alliance.

- CBT focuses on collaboration and active participation;you should view therapy as teamwork; together the doctor and patient decide what to work on each session, how often to meet, and what to do between sessions for therapy homework. At first, the physician may be more active in suggesting a direction for therapy sessions and in summarizing what's discussed during a session

- CBT is goal oriented and problem focused. You should ask in your first session for your patient to describe their problems and set specific goals so there is a shared understanding of what they are working towards.

- Self-perception is amenable to change through CBT

Agenda Setting

Just like how CBT is a structured-form of therapy, your sessions with your patient should also be structured and modeled on that. A typical CBT session should be structured as follows:[5]

CBT agenda based on a 60 minute session

| Time | Focus | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Before appointment | Assess symptoms | Patient fills out a scale assessing symptoms (GAD-7, PHQ-9, Beck) |

| 5-10 minutes | Check-in | What happened last week? Do a “mood check”: how is this week's mood compared to last week's? |

| 5 minutes | Set the Agenda | Decide: what are the important things that happened that need to be problem-solved today? Prioritize the agenda if there are many problems that happened. |

| 5 minutes | Bridge | Connect back to the last session: what was important during the last therapy session? |

| 5 minutes | Homework | Review homework done over the past week. |

| 30 minutes | Problem Solving | Focus on the core themes of CBT and problem-solve. |

| 5 minutes | Wrap up | Ask patient for feedback: How did the session go? Is there anything that bothered them or that they didn’t understand? Is there anything they'd like to see changed in future sessions? Assign homework for the next session |

Goal Setting

It is important for the patient to have specific goals they want to achieve by the time they are finished the course of therapy.

It is also important to have goals between sessions, that are more attainable and realistic. The “SMART Goals” framework is one way of achieving that.

S- SpecificM- MeasurableA- AttainableR- RealisticT- Time

Example of a SMART goal could be: “Add more structure to your day” – i.e. Make your bed, eat regular meals, have a regular sleep schedule, and make a regular schedule. Another SMART goal could be: “Have more social interaction by calling one friend each week.”

Homework

Homework is an integral part of CBT, and what makes CBT work. There are various types of homework assignments including:

- Behavioural activation

- Monitoring automatic thoughts

- Practicing new skills or implementing new solutions

- Reading assignments (like chapters in Mind Mover Mood)

When homework isn't done

You should ask yourself what is going through your mind when homework isn't being done. Remind yourself that you are not doing your patients any favours if you allow them to skip homework or don't encourage better compliance. The literature shows that patients who do homework assignments regularly have a better prognosis that paints who do not.[6]

Beginning CBT

Intake Assessment

- Identify your patient's current feelings (“I’m a failure, I can’t do anything right, I’ll never be happy”)

- Identify the problematic behaviours (isolating herself, spending a great deal of unproductive time in her room, avoiding asking for help). These problematic behaviours both flow from and in turn reinforce Sally’s dysfunctional thinking.

- What the precipitating factors that in influenced your patient's perceptions at the onset of their depression? (e.g., being away from home for the first time and struggling in her studies contributed to her belief that she was incompetent)

- Third, I hypothesize about key developmental events and how the enduring patterns of interpreting these events that may have predisposed your to their symptoms (e.g., your patient has had a lifelong tendency to attribute personal strengths and achievement to luck, but views her weaknesses as a reflection of her “true” self).

Session #1

- Introduce the name of the supervisor, if you have one

- Outline that there are tasks (“homework”) for each week, and doing the task is like taking medication. Homework is a vital part of therapy and it is important that the patient is aware of this in the first session.

- Buy a guide book, such as Mind Over Mood

- Outline that there are about 16 sessions in total, again, like medication, it is important to do this

- Get a journal to keep a thought record, and begin doing thought records early

- Photocopy the homework if possible

- Do scales for whatever disorder you're addressing:

- PHQ-9 or Beck Depression Inventory for Depression

- SPIN for Social Anxiety

- The way you think, affects how you feel and how you behave

- Identify specific problems, and set specific goals

- E.g. - problem = isolation, goal (is something behavioural) = start new friendships, and spend more time with existing friends

- During future sessions, and in discussing how to improve day-to-day routines, you will help your patient evaluate and respond to thoughts that interfere with the goals described above, such as: My friends won’t want to hang out with me,“ or “I’m too tired to go out with them.”

- You will help the patient evaluate the validity of her thoughts through an examination of the evidence. They should be able to test the thoughts more directly through behavioural experiments, where they initiate plans with friends. Once your patient recognizes and corrects the distortion in their thinking, they will benefit from more straightforward problem solving to decrease their isolation.

Homework to Assign after Session 1

- Define a goals list

- Begin a thought record. Remind yourself to be skeptical of these thoughts and that they may not always be true

- Be kind to yourself

- Think about things you want to bring up at the next session

- Organize an activity to do (this is “behavioural activation”)

Session #2

- Do a scale to quantify symptoms

- Set the agenda

- Review the homework from last time

- Thought records, behavioural activation

- Note any safety concerns

- Note any changes in therapeutic alliance, transference/countertransference

Guided Discovery Questions

- “What is the evidence that your thought is true? What is the evidence on the other side?”

- “What is an alternative way of viewing this situation?”

- “What is the worst that could happen, and how could you cope if it did? What’s the best that could happen? What’s the most realistic outcome of this situation?”

- “What is the effect of believing your automatic thought, and what could be the effect of changing your thinking?”

- “If your [friend or family member] were in this situation and had the same automatic thought, what advice would you give him or her?”

- “What should you do?”

When emotions are too much

Sometimes a patients emotions and thoughts are very valid, the question is how well do they cope with these feelings?

Session #3 and Beyond

Techniques

When evaluating situations that your patient brings up, here are some helpful techniques:

Piecharts

Use a pie chart to assess the pie chart contribution of the situation

Percentage Scales

- “If you are a terrible student, then where are you on this continuum,” “Are you a 100% terrible student? 50%? or 0%? Why that percent?” - “If you feel like you are a failure or people don’t love you, “How much of that do you think is true? 100%, 50%?”

Thought Records

- Rate the feeling

- which thought matches the emotion - the hot thought

- how much you believe in each thought

- which thought is the most therapeutic

- evidence for and against

Balancing Thoughts

The goal of CBT is to help your patients correct the hot thought, by reaching balance thoughts such as:

- Even though [i’m behind on my rent], I can see that [I have a solution now/and a capable person], because [I have support from my family].

Beware though, of superficial and “fake” balance thoughts. For example, if a patient is constantly worried about having anxiety because their hot thought is: “I’m a terrible mom.” and her balanced thought is “but I’m an good wife.” Notice that this balanced thought doesn't actually relate to the hot thought. If the balance thought does not correspond with the hot thought, that’s a giant pit fall the therapist must identify!

Socratic Questioning

Socratic questioning, or the socratic method, is a key technique in CBT. You help your patient understand themselves by asking questions about their thoughts, examples include:

- “What was going through your mind before you started to feel this way?”

- “What images or memories do you have of this situation?”

- “What does this thought mean about your future, and your life?”

- “What are you afraid might happen?”

- “What is the worst that could happen?”

- “What does this mean about how the other person thinks about you?”

- “What does this mean about the other person or people in general?”

- “Did you break rules, hurt others, or do something that you should not have done?”

- “What do you think about yourself about having done this, or thinking you did this?”

Terminology

CBT uses lots of different terminologies, and it can be helpful to spell out exactly what they mean, so both you and your patients can be speaking the same language.

Feelings

- Feelings are one word

- You're not a robot, you can't change feeling, but you can change thoughts and behaviours

Thoughts

- Thoughts are sentences

- Be skeptical of your thoughts!

- Sometimes your thoughts are right, but sometimes they can be wrong too

Automatic Thoughts

Although some automatic thoughts are true, many are either untrue or have just a grain of truth. Patients need a structured method to evaluate their thinking; otherwise, their responses to automatic thoughts can be superficial and unconvincing and will fail to improve their mood or functioning. Typical mistakes in thinking include:

Common Automatic Thoughts or Cognitive Distortions

| Type | Definition | Example |

|---|---|---|

| All-or-nothing thinking | Viewing a situation in only two categories instead of on a continuum. | “If I’m not a total success, I’m a failure.” |

| Catastrophizing | Predicting the future negatively without considering other, more likely outcomes. | “I’ll be so upset, I won’t be able to function at all.” |

| Emotional reasoning | Thinking something must be true because you “feel” (actually believe) it so strongly, ignoring or discounting evidence to the contrary. | “I know I do a lot of things okay at work, but I still feel like I’m a failure.” |

| Disqualifying or discounting the positive | Unreasonably telling yourself that positive experiences, deeds, or qualities do not count | “I did that project well, but that doesn’t mean I’m competent; I just got lucky.” |

| Labeling | You put a fixed, global label on yourself or others without considering that the evidence might more reasonably lead to a less disastrous conclusion. | “I’m a loser. He’s no good.” |

| Magnification/minimization | When you evaluate yourself, another person, or a situation, you unreasonably magnify the negative and/or minimize the positive. | “Getting a mediocre evaluation proves how inadequate I am. Getting high marks doesn’t mean I’m smart.” |

| Mental filter | “Because I got one low rating on my evaluation [which also contained several high ratings] it means I’m doing a lousy job.” | “Because I got one low rating on my evaluation [which also contained several high ratings] it means I’m doing a lousy job.” |

| Mind reading | You believe you know what others are thinking, failing to consider other, more likely possibilities. | “He thinks that I don’t know the first thing about this project.” |

| Overgeneralization | You make a sweeping negative conclusion that goes far beyond the current situation. | “[Because I felt uncomfortable at the meeting] I don’t have what it takes to make friends.” |

| Personalization | You believe others are behaving negatively because of you, without considering more plausible explanations for their behavior. | “The repairman was curt to me because I did something wrong.” |

| “Should” and “must” statements | You have a precise, fixed idea of how you or others should behave, and you overestimate how bad it is that these expectations are not met. | “It’s terrible that I made a mistake. I should always do my best.” |

| Tunnel vision | You only see the negative aspects of a situation. | “My son’s teacher can’t do anything right. He’s critical and insensitive and lousy at teaching.” |

Questioning Automatic Thoughts

- What is the evidence that supports this idea? What is the evidence against this idea?

- Is there an alternative explanation or viewpoint?

- What is the worst that could happen (if I’m not already thinking the worst)? If it happened, how could I cope? (What is the best that could happen? What is the most realistic outcome?)

- What is the effect of my believing the automatic thought? What could be the effect of changing my thinking?

- What would I tell [a specific friend or family member] if he or she were in the same situation?

- What should I do?

Thought Records

Reviewing the Thought Record

It is often very hard to describe what exact situation occurred when your patient describes their automatic thought to you weeks after the event. By that time, the patient often has had several days to think about their actions-thoughts-behaviours, and it can be easily to over-rationalize those thoughts. To get a better sense of the exact automatic thought and behaviours, it can be helpful to ask your patient: “replay everything back to me like a movie, down to the specific words exchanged and the conversation if you can.” This helps ground the patient on the exact situation at that time, and helps you better understand their thought process.

Resources

For Patients

- Mind Over Mood - Teaches skills and principles used in cognitive behavioral therapy, provides worksheets, assignments

- MoodGym - Interactive self-help program for preventing and coping with depression and anxiety; teaches self-help skills drawn from CBT