Table of Contents

Extrapyramidal Symptoms (EPS)

Primer

Extrapyramidal Symptoms (EPS) are drug-induced movement disorders that occur due to antipsychotic blockade of the nigrostriatal dopamine tracts. These blockades can lead to increased cholinergic activity, resulting in acute dystonia, acute akathisia, antipsychotic-induced parkinsonism, tardive dyskinesia (TD), tardive dystonia, and tardive akathisia.

Why Is It Called Extrapyramidal Symptoms?

The extrapyramidal and pyramidal tracts are the pathways by which motor signals are sent from the brain to lower motor neurones. The lower motor neurones directly innervate muscles to produce movement. The pyramidal tracts are involved in conscious control of muscles from the cerebral cortex to the muscles of the body and face. The extrapyramidal tracts (called “extra” to distinguish it from the tracts of the motor cortex that reach their targets by traveling through the pyramids of the medulla) originate in the brainstem, and carry motor fibres to the spinal cord. These tracts are responsible for the unconscious, reflexive or responsive control of musculature (e.g - muscle tone, balance, posture and locomotion). The reticulospinal tract is one of the most important extrapyramidal tracts for controlling the activity of lower motor neurons.Risk Factors

Antipsychotic naive individuals, the elderly, and those with intellectual disability are at greater risk for developing EPS.[1] In particular, elderly females are more likely to develop drug-induced parkinsonism and tardive dyskinesia, while young ethnic males are more likely to develop dystonic reactions.[2]

Scales

Rating Scales for EPS

| Name | Rater | Description | Download |

|---|---|---|---|

| Extrapyramidal Rating Scale (ESRS) | Clinician | The ESRS is the most comprehensive rating scale as it assesses for all types of EPS, while the other scales only assess for one domain. | Download |

| Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale (AIMS) | Clinician | The AIMS is a 12-item clinician-rated scale to assess severity of tardive dyskinesia (specifically, orofacial movements and extremity and truncal movements) in patients taking antipsychotic medications. | Download |

| Simpson Angus Scale (SAS) | Clinician | The SAS is an established instrument for antipsychotic-induced parkinsonism | Download |

| Barnes Akathisia Rating Scale (BARS) | Clinician | The BARS is the most commonly used scale to measure antipsychotic-induced akathisia in clinical trials. | Download |

Acute Dystonia

Acute dystonia is an acute movement disorder that can result from antipsychotic use. It occurs more commonly with typical antipsychotics, and can affect 3 to 10% of individuals. It can occur either immediately or within days of starting an antipsychotic. Acute dystonia is characterized by sustained contractions of the neck, orofacial muscles, or tongue (i.e. - opisthotonos, torticollis). When identified, it can be easily treated with an anticholingeric such as benztropine and will resolve.

Confusing Terminology Alert!

Dystonia can be both acute or tardive, therefore, you can have both acute and tardive dystonia (tardive dystonia is less common and much rarer). However, tardive dystonia is NOT the same as tardive dyskinesia. The difference is that there are sustained muscular contractions in tardive dystonia. An individual's posture is also abnormal in tardive dystonia.Pathophysiology

- A long time ago, before the introduction of dopamine agonists (e.g. - L-dopa), anticholinergics (e.g. - benztropine) were a very common treatment for Parkinson’s disease.

- Recall that Parkinson's disease caused by the destruction of dopamine neurons in the nigrostriatal region.

- Thus, this led to initial theories about Parkinson's that there is a reciprocal relationship between acetylcholine and dopamine in the brain.

- Anticholinergics were thought to improve Parkinsonian symptoms by increasing endogenous dopamine levels.

- Acute dystonia from antipsychotics is thought to occur through this pathway seen in Parkinson's.

- Normally, dopaminergic neurons in the nigrostriatal pathway have an inhibitory effect on cholinergic interneurons that regulate motor movements in the body.

- When dopamine antagonists (i.e. - antipsychotics) are given, this decreases endogenous dopamine.

- Since antipsychotics reduce dopamine's inhibitory effects, this results in increased firing of cholinergic interneurons, and increased release of acetylcholine.

- This combination of decreased dopamine (postsynaptic nigrostriatal dopamine blockade) and excessive acetylcholine is thought to create a dopaminergic-cholinergic imbalance that leads to development of extrapyramidal symptoms (including Parkinsonism).[3]

- This theory is supported by several observations: acute dystonia usually occurs after initiation of an antipsychotic agent, or an increase in dose. Acute dystonia is also less common in the elderly due to overall lower levels of dopamine (D2) receptor activity.[4]

- Conversely, when an anticholinergic drug (e.g. - benztropine) is given, this counteracts the excess cholinergic activity, and reduces acute dystonia and Parkinsonism.

- This is also why antipsychotics that are more anticholinergic (e.g. - clozapine, quetiapine) also have a lower incidence of EPS! They have “built-in” benztropine!

Airway Impairment

- In rare cases of acute dystonia, the diaphragm can also be involved, and there can be breathing compromise. Patients may also report a tense tongue or throat, another moderate sign of acute dystonia. If untreated, acute dystonia can progress to dysphagia, laryngospasm/pharyngospasm, leading to dyspnea.

- In rare, but severe cases, there can be asphyxia or choking.

Oculogyric Crisis

- Other rare presentations of acute dystonia include oculogyric crises, which can lead to permanent injury. On physical exam, patients in an oculogyric crisis have prolonged involuntary upwards deviation of the eyes bilaterally.

Treatment

- The offending antipsychotic should first be stopped. After, an intramuscular or oral anticholinergic such as benztropine can be given. In theory, any drug that blocks cholinergic activity (e.g. - an anti-parkinsonian agent) or drugs that increase striatal dopamine function (e.g. - certain atypical antipsychotics) can correct this dopaminergic-cholinergic imbalance and postsynaptic nigrostriatal dopamine blockade.

- Although the emergency use of benztropine for acute dystonia is very effective, benztropine should not be prescribed chronically or as a prophylactic measure. This practice is questionable and likely to cause more harm to patients than benefit. There are adverse effects from long-term use including cognitive impairment, increased dementia risk,[5] and worsening of tardive dyskinesia (in individuals who already have TD).[6][7]

- In the vast majority of cases, chronic prescriptions of benztropine can be safely discontinued with no worsening of risk for acute dystonia or movement disorders, along with improvements in cognition once benztropine is stopped.[8]

Treatment for Acute Dystonia

| Dose | Daily max | Onset of action | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Benztropine | 1-2 mg PO/IM q4h PRN for EPS | 6 mg | < 1 hour |

| Diphenhydramine | 25-50 mg po/IM/IV q4h PRN for EPS | 200 mg | 1-3 hours |

Akathisia

Akathisia (Greek: “Inability to sit”) is a neuropsychiatric syndrome characterized by the subjective feeling of anxiety, restlessness, and an irresistible urge to move.[9] Akathisia is an acute reaction, and occurs within hours to days of starting the offending agent. Individuals may feel compelled to pace and do tasks; for some, this can cause severe agitation, irritability, outbursts, and may place individuals at higher suicide risk.[10]

A Medical Student's Experience of Akathisia

“[Akathisia] was a diffuse, slowly increasing anxiety. My uneasiness soon began to focus on the idea that I could not possibly sit for the rest of the experiment. I imagined walking outside; the idea of walking was particularly attractive. I could not concentrate on what I had been reading. As soon as I could move, I found myself pacing up and down the lab, shaking and wringing my hands. Whenever I stopped moving, the anxiety increased. I imagined bicycling home rapidly - the thought of rapid motion was again appealing. I gladly washed a large pile of dishes that were not mine–normally not my favorite activity. Two features of this akathisia reaction impressed me. First, the intensity of the dysphoria was striking. Second, the sense of a foreign influence forcing me to move was dramatic. Long before I thought of akathisia, or even discovered that moving made me less anxious, I was pacing and wringing my hands. Had I been asked why I was behaving this way, I can imagine I would have looked at my hands and feet and responded “I don't know.” The sense of a foreign force driving one to move, with the concomitant anxiety, might be extremely disconcerting to an uninformed patient who is already struggling with psychosis.”– Kenneth S. Kendler, 1976 (after receiving 1mg IM haloperidol in an experiment)

Pathophysiology

- The etiology of akathisia is not well understood. It is thought that reduced dopamine transmission in the brain is responsible.[11] However, akathisia does not respond as as well to anticholinergic agents (compared to acute dystonia and pseudoparkinsonism), which suggests there is an alternative etiology.

Scale

- A commonly used rating scale for the measurement of akathisia includes the Barnes Akathisia Rating Scale (BARS) and Extrapyramidal Symptom Rating Scale (ESRS).

Physical Exam

- On examination, patients will appear unable to sit, stand, or lie still. When seated, their legs may cross and uncross frequently.

- When walking, the body weight may shift from one foot to another, or they may pace back and forth.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for akathisia is broad and includes:

- Agitation secondary to psychotic symptoms

- Non-akathisia antipsychotic dysphoria

- Agitation related to affective disorder

- Organic disorders (e.g. - delirium, head injury, hypoglycemia, encephalitis lethargica)

- Neurologic disorders (e.g. - Parkinson’s disease, Huntington’s disease)

- Tardive dyskinesia (commonly coexists with akathisia)

Management

- Prior to starting antipsychotics, prescribers should systematically assess for symptoms and signs of akathisia using a validated scale. Using a scale can allow providers to monitor for any emergent symptoms of akathisia.[12]

Treatment

- Treatment of akathisia includes reducing the dose of the offending agent, or treatment with benzodiazepines. Benzodiazepines (clonazepam, lorazepam, diazepam) can also be given prophylactically to reduce the incidence of akathisia.

- The use of anticholinergic medications such as benztropine should not be routinely used due to poor evidence and risk of side effects.[16]

- There is also limited evidence that Vitamin D6 can be used in persistent akathisia.[17]

Treatment for Akathisia

| Dose | Daily max | Onset of action | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Benzodiazepines (Clonazepam, lorazepam, diazepam) | Lowest possible dose | Lowest possible dose | 15-30 mins |

| Propranolol | 10-20mg PO | 120 mg | 1-2 hours |

| Mirtazapine | 15mg | 15mg | within 7 days |

Parkinsonism

Parkinsonism is a clinical syndrome comprised primarily of rigidity, tremor, and bradykinesia. The most common cause of parkinsonism is Parkinson disease, but parkinsonism also can occur because of the use of antipsychotics (more accurately referred to as medication-induced Parkinsonism, or pseudoparkinsonism, since the symptoms are not from a true Parkinson's Disease). It usually appears within a few days of starting treatment, or may evolve slowly over several weeks. Other causes of parkinsonism include Lewy Body Dementia, Wilson's disease, substance abuse, or Huntington disease, and must be ruled out.

Symptoms are similar to Parkinson's Disease, including bradykinesia, mask-like face, cogwheel rigidity, and tremors. Tremors are considered a cardinal sign of antipsychotic-induced Parkinsonism.[18] Other features of drug-induced parkinsonism include increased salivation, drooling, seborrhea, and postural instability. Approximately 40% of older patients treated with typical antipsychotics can develop drug-induced parkinsonism even at low doses.[19] Atypical antipsychotics have a lower incidence of causing parkinsonism.

Pathophysiology

The blockage of D2 receptors by antipsychotic drugs in the striatum is thought to lead to disinhibition of GABA and encephalin-containing striatal neurons in the indirect pathway without affecting the direct pathway in the basal ganglia, along with by disinhibition of the subthalamic nucleus. The change in the output of the indirect pathway of the basal ganglia-thalamocortical motor loop, is similar to changes seen in Parkinson disease.[20]

Treatment

Benztropine is commonly prescribed, but its use should be limited to short-term use, as there are significant adverse effect associated with long-term anticholinergic use, including: tachycardia, memory loss, blurred vision, urinary retention, and constipation. This is especially common in older patients. In general, the evidence is poor for the use of benztropine, though it is commonly used.

Tardive Dyskinesia

Tardive dyskinesias (TD) are involuntary movements of the muscles of the face, mouth, and tongue that are referred to as orofacial dyskinesias. These are repetitive oral, facial, and tongue movements that can resemble grimacing, chewing, lip smacking, tongue protrusion. The estimated prevalence of TD from exposure to antipsychotics is estimated to be 30% with first-generation antipsychotics, and 20% with second-generation antipsychotics.

- Non-modifiable risk factors include: older age, female sex, white/African ethnicity, prolonged illness duration, intellectual disability, brain injuries, negative symptoms in schizophrenia, mood disorders, cognitive dysfunction secondary to mood disorders, and gene polymorphisms in antipsychotic metabolism are all risk factors for developing TD.[21]

- Modifiable risk factors include: diabetes, smoking, and alcohol and substance abuse, antipsychotic selection, higher cumulative antipsychotic dosage, early parkinsonian side effects, anticholinergic burden, akathisia, and emergent dyskinesia.[22]

- TD movements disappear during sleep.[23]

– John M. Kane, M.D.

Withdrawal Dyskinesias

- Abruptly stopping an antipsychotic drug in any patient may cause a withdrawal-emergent dyskinesia (W-ED)!

Pathophysiology

Chronic blockade of dopamine receptors (in the nigrostriatal pathway) by antipsychotics results in dopamine receptor hypersensitivity and up-regulation of postsynaptic dopamine receptors.[25][26] The increase in dopamine receptors means there is hyperinhibition of the stop signal, in conjunction with unopposed go signals in the post-synaptic receptor. This is thought to generate the hyperkinetic movements observed in TD. Of note, this remains a theory and research is still ongoing. However, it remains a useful pathophysiological explanation for the development of tardive dyskinesias.

Physical Exam

Tardive dyskinesia movements can often be revealed or amplified by an activation technique since many patients need to be distracted before the disorder will visually manifest. For example, ask the patient to keep their mouth open for 20 to 30 seconds, then ask them hold up their hand while tapping each finger to the thumb in sequence. Another clinical exam is to ask the patient to open and close each hand while the mouth is open. This allows one to observe any curling or writhing movements of the tongue.[27] TD can persist even after discontinuing treatment, hence, it is very important to monitor for early signs of TD using the Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale (AIMS).

Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale (AIMS)

The Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale (AIMS) is a rating scale that was designed in the 1970s to measure involuntary movements known as tardive dyskinesia (TD).

EPS (Tardive Dyskinesia) Monitoring

| Name | Rater | Description | Download | Video |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale (AIMS) | Clinician | The AIMS is a 12-item clinician-rated scale to assess severity of dyskinesias (specifically, orofacial movements and extremity and truncal movements) | AIMS Download | Video Guide |

Treatment

Do not use benztropine to treat TD!

Benztropine should only be used for treatment of acute dystonia and Parkinsonism. Using benztropine for tardive dyskinesia can worsen/aggravate symptoms of TD.[28]- The first approach to treatment of tardive dyskinesia is either to stop the offending antipsychotic, reduce the dose, switch to a lower potency second-generation antipsychotic (such as olanzapine, quetiapine, clozapine, or asenapine).[29] Clozapine remains largely under-utilized, despite evidence of its superiority over other antipsychotics, and the lower risk of TD.[30]

- Adjunctive treatments can be added, such as tetrabenazine,[31] and with newer agents like the VMAT-2 inhibitor valbenazine.[32]

- Vitamin E may have minor beneficial effects on reducing the severity of TD.[33]

EPS Comparison

Table

Extrapyramidal Symptoms

| Symptoms | Onset | Risk Factors | Pathophysiology | Symptoms | Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acute dystonia | Within 5 days | Young Asian or Black males | Antipsychotic D2 blockade causes a dopaminergic-cholinergic imbalance (decreased dopamine, excess acetylcholine). | Sustained abnormal posture, contraction of muscle groups, muscle spasms (e.g. - oculogyric crisis, laryngospasm, torticollis) | Benztropine, diphenhydramine, stop offending antipsychotic |

| Akathisia | Within 10 days | Antipsychotic-naïve | Thought to be an imbalance between dopaminergic and serotonergic/noradrenergic neurotransmitter systems. Poorly understood. | Motor restlessness, crawling sensation in legs, distressing, increased risk of suicide and medication non-adherence | Benzodiazepines, propranolol, mirtazapine, reduce dose of antipsychotic |

| Parkinsonism | Within 30 days | Elderly females | Antipsychotic D2 blockade alters output of the indirect pathway of the basal ganglia-thalamocortical motor loop, similar to changes seen in Parkinson disease. | Cogwheel rigidity, tremors, postural instability, stooped posture, shuffling gait, en bloc turning | Benztropine, reduce dose of antipsychotic |

| Tardive dyskinesia (TD) | After 3 months | Chronic antipsychotic use | Chronic blockade of dopamine receptors (in the nigrostriatal pathway) by antipsychotics results in dopamine receptor hypersensitivity in the post-synaptic receptors, resulting in hyperkinetic movements. | Purposeless, constant writhing movements involving facial muscles, less commonly limbs | Reduce antipsychotic dose, switch to clozapine, or treatment with valbenazine or tetrabenazine |

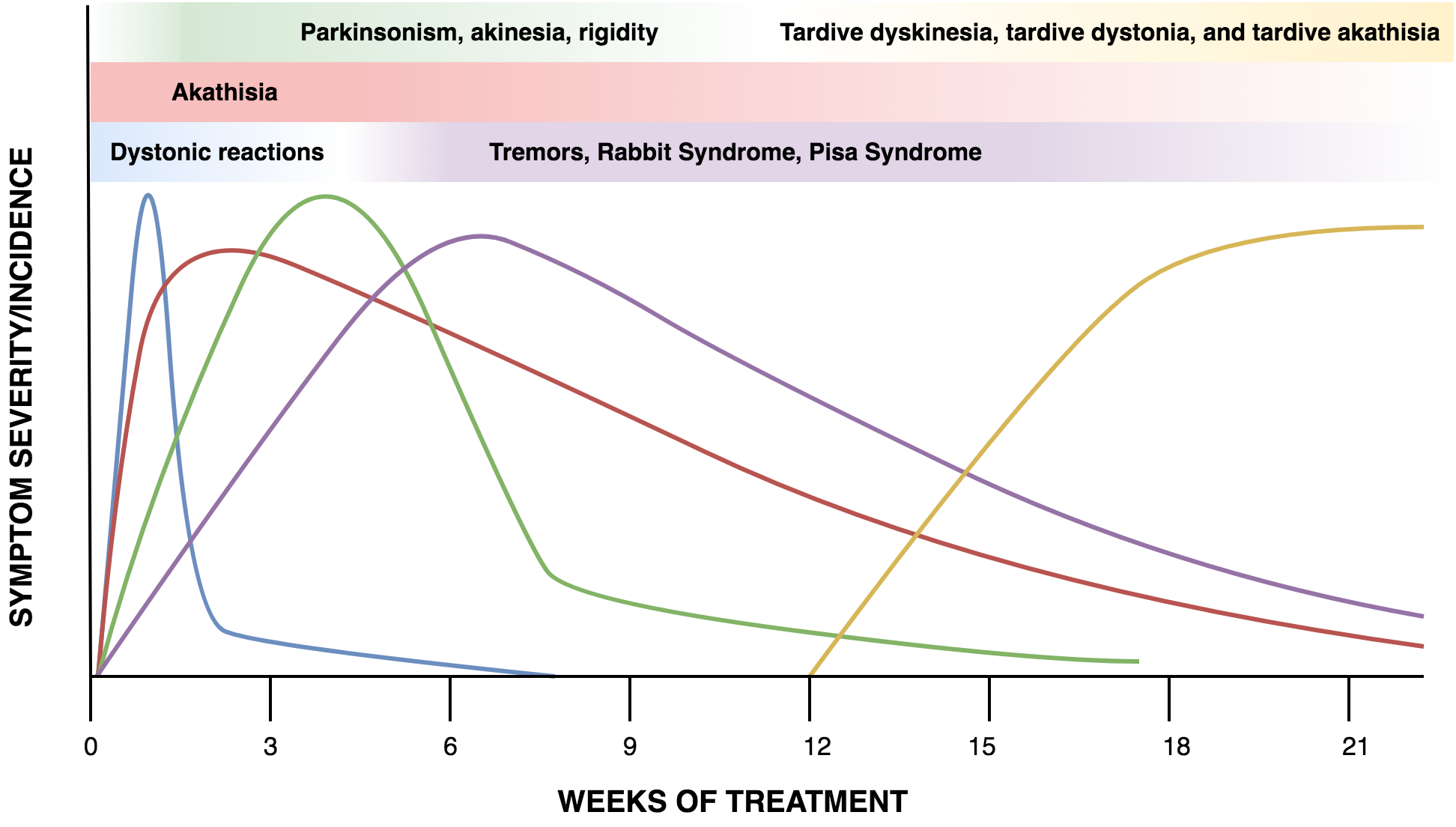

Time of Onset

The figure below (figure 1) shows the timeline of EPS over time.

Fig. 1

Fig. 1