Table of Contents

Approach to On-Call Internal Medicine Emergencies and Issues

Primer

Common Internal Medicine issues and emergencies for psychiatric patients may occur. It is important for any psychiatrist to have a good approach to these issues and to direct the right work up and medical care and not confound psychiatric symptoms with acute medical issues.

Physical Exam

- Never forget that a good physical exam is critical, so brush up on your general exam skills!

Vital Signs

Never forget the vital signs because they are vital. Always remember the A-B-C-Ds:

- Airway: Threatened airway, stridor, excessive secretions

- Breathing: RR ≤ 8 or ≥ 30, distressed breathing, saturations < 90% on ≥50% 02 or 6L/min

- Circulation: Systolic blood pressure ≤ 90 mmHg or ≥ 200 mmHg or decrease >40 mmHg, HR ≤40 or ≥130

- Disability: Decreased level of consciousness (GCS decrease ≥2 points)

- Other: Urine output ≤100 cc over 4 hours (except dialysis patients)

The Unresponsive Patient

- Look at the chest

- Listen for breath sounds

- Feel for carotid pulse (no longer than 10 seconds)

- No respiratory effort, no pulse → Call

CODE BLUEand start CPR. - Respirations and pulse present → Take vitals to assess for airway compromise, breathing insufficiency, and hypotension

Neurologic

See main article: Approach to Neurologic Emergencies

Altered Level of Consciousness or Delirum

See main article: Approach to Neurologic Emergencies: Altered Level of Consciousness

See main article: Delirium

Stroke

See main article: Approach to Stroke

Seizures

See main article: Approach to Seizures: Treatment

- If you witness a seizure, call for help, as the patient will likely have decreased LOC following the event. It is appropriate to call a code blue (“Medical Emergency”) if you need medications or more support.

- The first line treatment is with benzodiazepines either IV (preferred or IM). Give lorazepam 2mg, or midazolam 2mg, or diazepam 5mg q2-5minutes PRN until seizures are controlled.

- If not already on antiepileptics, it is reasonable to load them with dilantin (20mg/kg) to prevent further seizures.

Chest Pain

Initial

- Assess the patient

- Monitor the vitals closely over time

- Empirically order CK, troponins, ECG

- Chest X-Ray should also be considered if relevant

- Can also empirically order Tylenol, morphine to temporize pain (if there are no contraindications to the above)

Physical Exam

- Inspect, palpate, auscultate

- Is the pain positional?

- What is the quality of the pain? (Sharp and stabbing?)

Differential Diagnosis

- Differential diagnosis should include non-cardiac causes! The top two serious causes to rule out on a medical ward are pulmonary embolism and MI, while the most common causes of chest are costochondritis (musculoskeletal chest pain) and GERD.

- Think cardiac, thorax (not heart), chest wall, GI

- This includes myocardial infarction, pulmonary embolism, aortic dissection, pericarditis, tension pneumothorax, esophageal rupture

- These are important things to not miss! A severe presentation of any of the above (except for a pulmonary embolism) will also come with other signs and symptoms (the patient will look very unwell or also have other abnormalities on their vital signs)

Investigations

- ECG

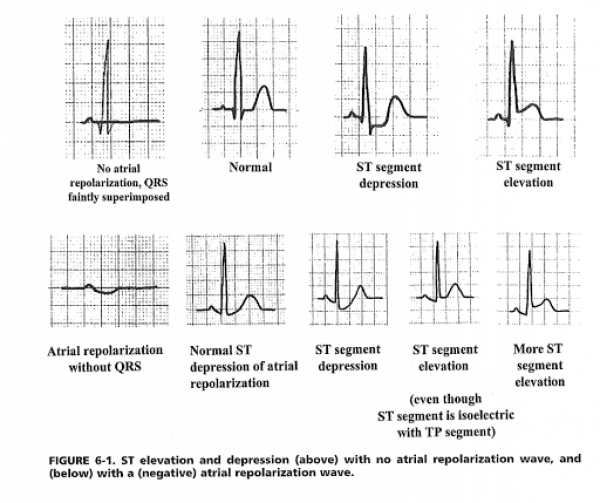

- ST segment elevations greater than 0.5mm and ST segment depressions greater than 1mm in 2 or more consecutive leads, or new left bundle branch block (LBBB) are concerning

- Most common false positive would be repolarization defects due to large voltages

- Always compare to a previous ECG if available. You don’t have to understand all the nuances of an ECG tracing but you need to look for changes, and for ST segment deviations.

- Troponin

- Troponins are NOT a substitute for clinical suspicion of an MI.

- Interpretation of troponin levels can be difficult. Troponins have high sensitivity (i.e. - good at ruling out an MI), but low specificity. A negative troponin and a stable troponin lets you rule out MI, but a positive one does not let you rule it in. Troponin elevations can either be “false positives” (chronic kidney disease, intracranial process, sympathetic stimulation), poor prognostic markers of non-ischemic disease (e.g. pulmonary embolism), or true indicators of ischemia (demand ischemia, NSTEMI, STEMI)

- Can order a serial CK and troponin in 4 hours to see if it trends upwards

- A normal CK but elevated troponin is less likely to be an NSTEMI or STEMI

- Chest X-ray (CXR)

- The main indication for a CXR is mainly to rule out a pneumothorax, which is why it is not necessarily always included the work-up. You could also order a CXR to rule out a rib fracture, pleural effusion, or pneumonia.

Management

Management of Chest Pain

| Management | Pearls | |

|---|---|---|

| STEMI | Call a code STEMI. Give ASA 160mg, clopidogrel 300-600mg or ticagrelor 180mg loading dose, and unfractionated heparin or low molecular weight heparin (consider bleeding risk, can choose fondaparinux). Pain can be managed with morphine. Oxygen should also be given. | Less likely to be MI if the pain is reproduced on palpation |

| NSTEMI | Can use the same medications as above for STEMI | Less likely to be MI if the pain is reproduced on palpation |

| Pulmonary Embolism (PE) | PEs are notoriously difficult to detect, but you must be aware of when it could happen! CTPE can be ordered (The risk of contrast-induced nephropathy is negligible if the patient does not have an AKI or CKD (roughly as long as Cr < 100 you are OK), else you have to think twice about it). Anticoagulation is the first-line treatment (see side-bar for more details). | If the pain is pleuritic with respiration, consider a pulmonary embolism. Any new or worsening tachycardia plus hypoxia with no ECG changes should make you suspect a possible PE. In conjunction with a normal CXR, this would be enough to treat empirically with anticoagulation |

| GERD | Should be a diagnosis of exclusion in new-onset chest pain. Treat with Almagel (magnesium hydroxide) or ranitidine |

PE Patients Can Become Rapidly Unable

Any sign of hemodynamic instability should prompt involvement of a rapid response team. These patients can be quite tenuous and deteriorate quicklyPEs, Anticoagulation, and CTPEs

Here are some clinical pearls to think about in the management of PEs:- Anticoagulation does not necessarily need to be started right away, even if you order a CTPE. However, in a severely ill patient with significant symptoms or hemodynamic changes, (such as tachycardia, hypoxia, and normal CXR), then you should more urgently

- Subsegmental PEs are controversial and may not account for your patient’s pain

Anticoagulation

Here are some tips for dosing depending on the type of heparin you choose:- Unfractionated heparin

- The nomogram seems confusing but in essence: more heparin makes blood thinner, and less heparin makes it less thin. The nomogram provides dose guidance for this. Look for the patient’s weight on the left, and choose a loading dose based on weight if you want them anticoagulated faster. Check the PTT q6h and adjust increase or decrease the infusion rate. Generally, you want a high dose nomogram for treatment and a low dose nomogram if you are concerned about bleeding risk

- Low-molecular weight heparin (LMWH)

- Enoxaparin 1mg/kg SC will last for 12h

- Tinzaparin 175u/kg SC rounded to nearest cartridge dose

Tachycardia

- First question is always “is the patient stable?”

- If unstable:

- Call a

CODE BLUEor activate Rapid Response

- If stable:

- What is the rhythm of their pulse?

- Get an ECG

ECG Strip Reading

Is the QRS narrow or wide?- If wide: it is VT until proven otherwise

- If narrow: it is either sinus tachycardia vs SVT

- Sinus tachycardia

- ECG shows: P before every QRS, QRS after every P, P is upright in leads I, II, PR is fixed

- Differential diagnosis: Pain, agitation, withdrawal, sepsis, volume depletion, PE, heart failure, pain, agitation, withdrawal, sepsis, volume depletion, heart failure

- SVT

- Most commonly will be due to Atrial fibrillation (AF) or Atrial flutter

- How fast is the HR?

- Are they on rate control agents already?

- Again, if unstable, call for help!

- Think of why this is happening! Treat underlying cause first, rather than just increasing meds

Atrial Fibrillation

A HR <110 is acceptable. Don’t need to be aggressive unless there are ischemic symptoms (angina, troponin bump, ECG changes, etc).

Respiratory Distress

- Check vital signs (O2 saturation, respiratory rate)

- Raise the head of the bed

- Call the respiratory therapist!

- If patient requires 50% of more FiO2 and you expect it to stay as is or deteriorate, then call the rapid response team and consider transfer to ICU

- Verify what kind of supplemental oxygen is being given:

- Nasal prongs (low flow – change)

- Face mask (low flow – change)

- Venturi mask (higher flow, color coded, 50% FiO2 is orange color)

- Non-rebreather “100% - although really is not”

- Optiflow – high flow nasal cannula with FiO2 up to ‘100%’ though with air entraining it is much less.

- ABGs are useless in an acute respiratory emergency

- If the patient is already desaturating or having low normal saturation on high FiO2, then they are hypoxic

- Doing an ABG will NOT help you in this acute situation.

- You may send a VBG if a RN is taking blood work, and this would be to rule out a hypercapnic component to the respiratory failure

- Common, non-serious causes of dyspnea or desaturation includes heart failure, COPD, asthma, atelectasis, or anxiety

Urgent and Emergent Causes of Dyspnea or Desaturation

| History and Physical | Investigations | |

|---|---|---|

| Pneumothorax | Hyperresonance, poor a/e, tracheal deviation | CXR (if hypotensive, aspirate immediately) |

| Myocardial Infarction | Rapid onset, cardiac RFs, Hx CAD, chest pain | ECG, serial troponin |

| Pulmonary Embolus | Wells Criteria for PE | D-dimer, CT-PA |

| Heart failure | Hx HF, ↑ JVP, crackles, edema | BNP, CXR, ECG |

| Severe asthma | Hx asthma, wheezing | Trial of B-agonist |

| COD exacerbation | Hx COPD, wheezing | CXR, ABGs, peak flow |

| Anaphylaxis | New meds or exposures, angioedema, ↓ BP | N/A |

| Severe anemia | Pallor, tachycardia | CBC, Crossmatch |

| Septic pneumonia | Fever, tachycardia, ↓ BP | CXR, blood cultures |

| Metabolic acidosis | Ingestions, renal pt, T1DM | ABG, lytes, Cr, glucose |

Hypotension/Hypertension

When managing issues around blood pressure, there are only four possible scenarios:

- Hypotensive Bad: BP is low and the patient is dying!

- Hypotensive Fine: BP is low, patient is fine, should we hold antihypertensives?

- Hypertensive Fine: BP is high, patient is fine, do we treat with antihypertensives?

- Hypertensive Bad: BP is high, and patient is having associated symptoms

Hypotension

Red Flags for Acute/Critical Care Involvement

- 4 Red Flags:

- Always treat the patient and not the number; vitals are sensitive but not specific

- Altered level of consciousness

- Trend of blood pressure getting progressively lower

- Decreasing urine output

- Management

- If due to sepsis, give more IV fluids and repeat lactate

- If due to dehydration, give IV fluids (consider 0.9% NS to avoid inducing hyponatremia)[1]

- If due to heart failure (especially if patient is hypoxic from heart failure), do not give more IV fluids

Urgent and Emergent Causes of Hypotension

| History and Physical | Investigations | |

|---|---|---|

| Hypovolemia | Tachycardia < 150, ↓ urine output, ↓ JVP | Cr, BUN, lactate, Group&Sc, Xmatch |

| Anaphylaxis | Exposure to agent, SOB, wheezing, angioedema | Clinical Dx (act quickly), give 0.3 mg IM epinephrine |

| Sepsis | Fever, source of infection (skin, resp, abdo, urine) | CBC, U/A, CXR, U/S, blood and urine, C&S |

| Arrythmia/cardiogenic shock | Palpitations, pulse irregular, dyspnea, ECG | ECG |

| Cardiac tamponade | Beck's triad - muffled heart sounds, ↑ JVP, hypotension | ECG, CXR, Echo |

| Pulmonary embolus | PERC, Wells criteria for PE | D-dimer, CT-PA |

General Management of Hypotension

- When there is low blood pressure, everyone manages the use of antihypertensives differently.

- Always treat the patient, not the number.

- Consider why they are on the antihypertensive to evaluate the risk/benefit to the patient of holding the medication.

- If you are not familiar with the patient, take the time to go over the trend of vitals in their chart prior to deciding.

Stopping Antihypertensives

| Easy to Stop | • Calcium channel blockers (amlodipine) • ACE inhibitors (-prils) • ARBS (-sartans) • Hydrochlorothiazides |

|---|---|

| Harder to Stop | • Beta blockers (generally do not cause that much hypotension and may be important in avoiding tachyarrythmias such as atrial fibrillation which may worsen heart failure) • Furosemide (may be needed in ongoing treatment of heart failure) |

Hypertension

Hypertensive Urgency vs. Emergency

| Hypertensive Urgency | Hypertensive Emergency/Crisis | |

|---|---|---|

| BP | SBP > 180 DBP > 120 | SBP > 180 DBP > 120 |

| Presentation | • Asymptomatic or no evidence of end-organ damage • Use PO meds to decrease by 25-30% Outpatient management | Evidence of end organ damage: CNS (altered LOC, asterixis), cardiac, renal, papilledema. |

| Treatment | Outpatient management. Use PO meds to decrease BP by 25-30%. | Inpatient management. Use IV meds to decrease BP by 25-30%. |

| Medications | In a patient with HTN pick hydrochlorothiazide over furosemide. But for patients with acute congestive heart failure, Lasix (furosemide) is superior to HCT | Hydralazine, captopril, labetalol IV (continuous infusion), nitroglycerin patch |

| Example | Will want to lower BP to 160/100 using PO meds | Nitropatch 0.8mg + labetalol 20mg IV (0.5mg/min infusion) |

When Should You Really Worry About High Blood Pressure?

- SBP > 180 AND there are signs of end organ damage (i.e. - headache, visual change, chest pain)

- Here you might actually treat the number and less so the patient. The only situation where you would allow the blood pressure to remain high is if it is a post-stroke patient

- If the SBP > 180, but they are asymptomatic, don't panic

- You have time (24 hours) to treat the high blood pressure, and in fact you may not want to treat too quickly, especially if they have been hypertensive for a long time

Treating and Managing Asymptomatic Hypertension

- Review current medications

- Can give an extra dose, titrate up current regimen or give AM dose early depending on clinical situation

- Adding agents

- Most of these will not act immediately, but again unless it is an emergency there is no need to lower urgently

- Beta blockers are NOT good antihypertensives

- Calcium channel blockers: amlodipine (5mg and go up in 2.5 to 5 mg increments)

- Thiazide diuretics: hydrochlorothiazide (12.5mg and go up by 12.5mg increments)

- ACE inhibitors: ramipril (2.5mg BID and go up by 2.5 mg increments, stop at 10 mg)

- Vascular smooth muscle dilators: hydralazine (5mg-10mg TID and go up in 5mg increments), good in renal failure. More rapid acting, can give an extra dose if needed.

Glucose Abnormalities

Hyperglycemia

See also:

- Hyperglycemia is usually of little significance acutely unless the patient is in diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) or in a hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state (HHS) from it, and that usually requires at least a few day's worth of insulin deficiency before this happens.

- Diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) or hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state (HHS) are the most serious, acute metabolic complications of diabetes, but other differentials include dietary indiscretion and new onset or uncontrolled diabetes

- DKA is a state of absolute insulin deficiency, hyperglycemia, anion gap acidosis, and dehydration. It classically occurs in younger patients (<65 years) with Type 1 diabetes and usually evolves rapidly over 24 hours. The most common causes are infections, disruption of insulin therapy, or as the presentation of new onset diabetes.

- HHS is a state of hyperglycemia, hyperosmolarity, and dehydration without significant ketoacidosis. It is typically seen in Type 2 diabetics, and has a higher mortality rate compared to DKA, and occurs in older patients. It most commonly occurs in older patients (>65 years old) with infections and/or poorly controlled Type 2 diabetes and evolves over several days.

- Both DKA and HHS originate from a reduction in insulin and an increase in counter-regulatory stress hormones.

- The key here is that in DKA the patient will be acidotic (low bicarb, high anion gap). In the context of positive ketones and known diabetes – this is DKA regardless of the glucose value (euglycemic DKA is possible and has a much higher incidence with SGLT2 inhibitors)

Mnemonic

The 6I's can be used to remember the I’s of DKA and HHS:I- Insulin deficiency (New onset T1DM, failure to take enough insulin)I- Infection is the most common precipitating factor (Pneumonia, UTI)I- Ischemia or Infarction (MI, CVA, Acute Mesenteric Ischemia)I- Inflammation (Pancreatitis, Cholecystitis)I- Intoxication (Alcohol, Drugs)I- Iatrogenesis (Glucocorticoids, Thiazides)

- Correcting Hyperglycemia

- You will likely be paged for blood glucose >20 because that’s how the default sliding scale orders are written

- Consider calling the hospital pharmacist if available to help with insulin dosing as well.

- Easy version: just give the maximum dose according to the sliding scale, or just give 2 units of insulin and ride it out

- Most sliding scales will have insulin Lispro (fast-acting insulin)

- Before administration of insulin, always ask:

- When was the last meal or snacks?

- What are the vitals?

- Look at the blood sugar trends over past week and baseline (if available)

- Remember that treating hyperglycemia can cause potassium shifts and may result in ECG abnormalities

- Most individuals with hyperglycemia will in fact be asymptomatic

- The classic symptoms that you should ask about include:

- Polyuria

- Polydipsia

- Polyphagia

- Weight loss

- Ask about symptoms of DKA:

- Abdominal pain

- Hyperpneic respirations (fast and deep Kussmaul respirations)

- Hypotension

- Ketotic breath (fruity odor in DKA)

- Marked tachycardia (in patients with marked acidemia or severe hyperglycemia, extracellular potassium shifts may result in ECG manifestations of hyperkalemia despite total body losses)

- Neurologic symptoms (seizures, focal weakness, lethargy, coma, death)

General Blood Sugar Targets

- General Blood Sugar Targets

- Pre-prandial goal: 5-8

- Random blood glucose: <10

- Start correcting if the BG > 10

- Wait about 2 hours after eating or insulin administration to check the blood glucose again

Insulin Types

| Class | Examples | Onset | Peak | Duration | Uses |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rapid Acting | Lispro/Humalog Aspart/Novorapid Glulisine/Apidra | 15 minutes | 1 to 2 hours | 4 hours | “Bolus” insulin: for glucose elevations related to meals/carb intake, or to correct high BG |

| Short Acting | Regular or Toronto (Humulin R or Novolin R) | 30 minutes | 2 to 4 hours | 6 to 8 hours | “Bolus” insulin: for glucose elevations related to meals/carb intake, or to correct high BG *Used for insulin infusions |

| Intermediate Acting | NPH (Humulin N or Novolin N) | 1 to 2 hours | 8 hours | 12 to 18 hours | “Basal” insulin: for glucose elevations related to hepatic glucose production in fasting state *Peak can cover lunch |

| Long Acting | Detemir/Levemir Glargine (Lantus, Toujeo) | 1 to 2 hours | None | 12 to 24> hours | “Basal” insulin: for glucose elevations related to hepatic glucose production in fasting state |

Hypoglycemia

- Hypoglycemia is much more concerning than hyperglycemia because there is a risk for seizures, decreased LOC, and cardiac events

- Immediate treatment is to ask the nurse to give juice/sugars

- Stop all sulfonylureas

- Reassess the patient's insulin orders

- Otherwise, you need to know how to push D50W (also for shifting hyperkalemia) to resolve this as it doesn’t come with a fluid load like running D5W or D10W does and it works the fastest

- Ask for an amp of D50W (50mL), the amp comes with both a needle as well as a Luer Lock tip

- Attach this to a port, pinch upstream of the port, and push it in gradually - the stuff is very sticky so it takes about 2 minutes to push it

- Blood glucose should go up by about 5-10 points after an amp of D50W

- Causes of Hypoglycemia

- In hospital, it will almost always be due to excess insulin administration so you should come down on any insulin dose they are on; remember Type 1 diabetics cannot have their basal insulin fully stopped

- Other causes include sulfonylureas, liver failure, renal failure, adrenal insufficiency, sepsis.

- It is very rarely due to an insulinoma (all other causes should be considered first) but if this is a patient with ongoing refractory hypoglycemia (i.e. - unlikely to be a new problem overnight) this can be considered, and ICU should likely be involved for monitoring at the least.

Electrolyte Abnormalities

See also main articles on: Hypocalcemia, Hypercalcemia and Hyperparathyroidism, Hypokalemia, Hypomagnesemia, and Hyponatremia

Hyperkalemia

- Check first, was the sample hemolyzed (i.e., falsely elevated potassium)?

- In hyperkalemia, you usually need to shift potassium. But this depends on the urgency; remember, the question is which way do you think the potassium is going to go? Is it going to stabilize, improve, or get worse without your intervention?

- If K = 6 or greater, order an ECG and consider calcium gluconate 1g IV for myocardial protection

- Check other electrolytes and glucose

- Remove or hold offending medications (ACE, ARB, spironolactone, Septra, tacrolimus)

- Think of precipitating conditions (renal failure, volume depletion, TLS)

- Consider whether this could be a hemolyzed sample – in doubt can always send a STAT repeat.

- If they have urine output and you’ve removed potassium sparing medications, put them on a low potassium diet, and their potassium is <5.5, you can just repeat potassium in 4 hours

- When in doubt (e.g. new renal failure, low urine output), then shift to deal with it earlier rather than later

- Shifting

- First, 1 amp of D50W

- Insulin regular IV 10u x1 (if potassium is not critical, e.g. <5.5, you can use subcutaneous insulin if need be), you can inject the insulin needle through a luer lock port

- Follow up the bloodwork in 4 hours, the shifting should cover you for 8 hours (if the patient is unable to excrete K – ie renal failure – the K will have peaked back up by then)

- Other short term options – inhaled beta-agonists (shift), HCO3 if the patient is acidemic (shift), fluids with lasix chase (eliminate).

- Longer term management for require increasing elimination and can be achieved with Lasix, laxative (we prefer lactulose) or dialysis depending on the clinical situation.

- If renal failure and refractory HyperK in the acute setting, nephrology should be involved for dialysis.

Hypokalemia

- If K < 2.5, then order an ECG and pay attention to QT segment

- Always order extended electrolytes and replace magnesium if low

- As much as possible, replace by ORAL route – much quicker than IV

- K 3.0-3.4, give KDur 40 x1

- K 2.5-3.0, give KDur 40 x2 (separated by 4hrs)

- K 2.0-2.5, give KDur 40q4h x3

- If unable to tolerate oral intake (dysphagia, LOC, etc.) first consideration should be the insertion of an NG tube in order to give oral K (especially if low K<2.5)

- IV options

- NS with 20-40mEq/L – identify rate and specific duration of therapy

- You will need to give a whole liter of fluid before you can administer the equivalent of one dose of Kdur – prioritize the oral route!!

- Consider holding any diuretics

Hypomagnesemia

See also: Hypomagnesemia

- Can also be due to alcohol intake, proton pump inhibitor use, or diarrhea.

- Consider replacing:

- If critically low (<0.5): order an ECG to assess QT segment

- Treat with MgSO4 2-4g IV in 200-400cc D5W over 2-4hours (all respectively). The nurses will often know the protocol and ordering MgSO4 2g IV should be sufficient

- Note that oral Mg can also cause diarrhea!

Hypophosphatemia

- Common causes include alcohol use or minimal oral intake

- Replace as needed

- If non-critical: replace with phosphate Novartis 500mg PO

- If critically low: check K, then replace IV with KPhos 15mmol in 500cc D5W if K < 3.5, OR use NaPhos 15mmol in 500cc D5W if K > 3.5

Hypernatremia

- This is a problem of water balance (too little), can be common in dementia patients

- Give them water to drink by mouth

- Again, unlikely to be acute issue overnight

- If NPO give them IV D5W. Stop normal saline.

- Slow infusion of D5W if within goals of care is appropriate (in the event that patients are unable to take water by mouth)

- Avoid rapid correction due to risk of cerebral edema

Hyponatremia

See also: Hyponatremia

- Not the same principle of replacement as in other electrolytes! Sodium imbalances are a problem of water imbalance

- Most issues of hyponatremia overnight will be chronic and best managed with a fluid replacement or restriction strategy

- So long as Na > 122, do not worry too much if overnight and on-call

- Hold any diuretics

- Order urine electrolytes and urine osmolality

- Safest action overnight is to do nothing unless there are acute signs and symptoms of deterioration

- If acutely hyponatremic (Na < 120), and there are complications such as seizure or mental status change, the patient needs hypertonic saline and ICU/neprhology involvement

- Avoid rapid correction 6-8/24h for risk of osmotic demyelination syndrome

Pain

See main article: Pain Medicine

- What is the etiology of the pain?

- Is the patient already on pain medication?

- Do they need new medications?

- Order standing tylenol 1g PO QID – (none or lower dose if liver failure)

- Adjunctive treatment

- Gabapentin 300mg

- Pregabalin 25mg

- Voltaren (topical NSAID) great for MSK pain

- Generally avoid NSAIDs in the older patient population. Give to younger patients (<50) with no history of renal failure

- Opioids (avoid if possible, start at low dose always)

- Hydromorphone 0.5mg PO x 1 (or if there is severe pain, can order recurring q4h PRN)

- Increase dose of current medications?

- Patients on opioids should have breakthrough PRNs already ordered.

- Do not increase long acting or give extra dose of long acting overnight. This should be done by reviewing the total number of breakthroughs used and can be done in the morning with the team

Insomnia

See main article: Insomnia Disorder

- Always try non-pharmacological interventions first

- Earplugs

- Eye mask

- Are there other sources of environmental disturbance?

- If a patient is chronically on a benzodiazepine at home, do not stop them abruptly

- Can trial melatonin 3mg PO qHS (though there is poor evidence for use of melatonin in insomnia)

- If absolutely needing to using Z-drugs, use half-doses (e.g. zopiclone 3.75mg instead of 7.5mg)

- Use your clinical judgment

Constipation

- Assess the timeline of symptoms

- Constipation is only an emergency if there is impaction with large fecaloma (bacterial translocation, mucosal ischemia)

Treatment

See main article: Constipation

- Lactulose (30cc PO can give BID) or PEG 3350 (17g PO) are most effective. Never use docusate sodium (Colace), it is not an effective drug!

Urinary Tract Infections

- Do not treat asymptomatic bacteria in the elderly.[2]

Other Lab Abnormalities

- Elevated WBC

- 50% of the time this is NOT due to infection (e.g., stress reaction, steroids)

- Elevated hemoglobin

- Often hemoconcentrated. Differential diagnosis is hypoxia (from COPD), EPO, renal (NOT CKD), adrenal (Cushing's)

- Low hemoglobin

- If < 70 they need iron and likely blood

- If 70-80 & no active bleeding maybe hold antiplatelet/anticoagulant.

- New thrombocytopenia in hospital

- 90% of the time = sepsis, medication related, or HIT [heparin induced thrombocytopenia]

- Low ferritin

- Ferritin < 50 is likely iron deficiency. If old, think cancer. If young woman, think menorrhagia (consider OCP)

- High ferritin

- Any inflammatory condition, including critical illness

- Other causes include alcohol use, NASH, hepatitis

- Low B12

- Autoimmune causes (e.g. - pernicious anemia), malabsorption (e.g. - gastric bypass), meds (e.g. - metformin)

- High B12

- cirrhosis, liver cancer or mets, myeloproliferative disorders, critical illness

- Prolonged PT

- Often artifact. If bleeding think anticoagulant med (e.g., DOAC), liver disease, hemophilia.

- Prolonged aPTT

- Often artifact. If bleeding think: anticoagulant med, liver disease, hemophilia, APLA

- Are PT/aPTT good coagulation tests? No!

- LTFs

- High AST

- The S stands for Sometimes it is from the liver (ddx, rhabdo, viral infection, celiac, toxins, meds, etc.)

- High ALT

- The L stands for Liver (work them up accordingly)

- High ALP

- Biliary (stone, infection, inflammatory, cancer), bones (cancer, Paget's), liver, pregnancy.

- High bilirubin

- Biliary causes, liver (cirrhosis), heme (hemolysis, transfusion), inherited disorders (Gilbert's), sepsis.