- Last edited on March 4, 2021

DiGeorge (22q11.2 Deletion) Syndrome

Primer

DiGeorge Syndrome (also known as 22q11.2 Deletion Syndrome, and formerly Velocardiofacial Syndrome) is a syndrome caused by the deletion of a small segment (microdeletion) of chromosome 22. It is the most common microdeletion syndrome in humans. This microdeletion is also responsible for a 20 to 30 times increased risk for schizophrenia, which equates to 1 in 4 individuals developing schizophrenia. Thus, 22q11.2 deletion is considered to be the first true molecular genetic subtype of schizophrenia. In addition, individuals often have congenital heart problems, facial dysmorphia, developmental delay, learning problems, and cleft palate. Renal impairment, hearing loss, infections, and autoimmune disorders are also common.

Epidemiology

- DiGeorge syndrome has a prevalence of 1 in 4,000 people.[1] Individuals are also at a higher risk for early-onset Parkinson's Disease.

Risk Factors

- 90% of cases are usually new diagnoses with no identifiable family history. Genetically, there is variable expression of the deletion within families, and even between identical twins.

What the Heck Does 22q11.2 Mean?

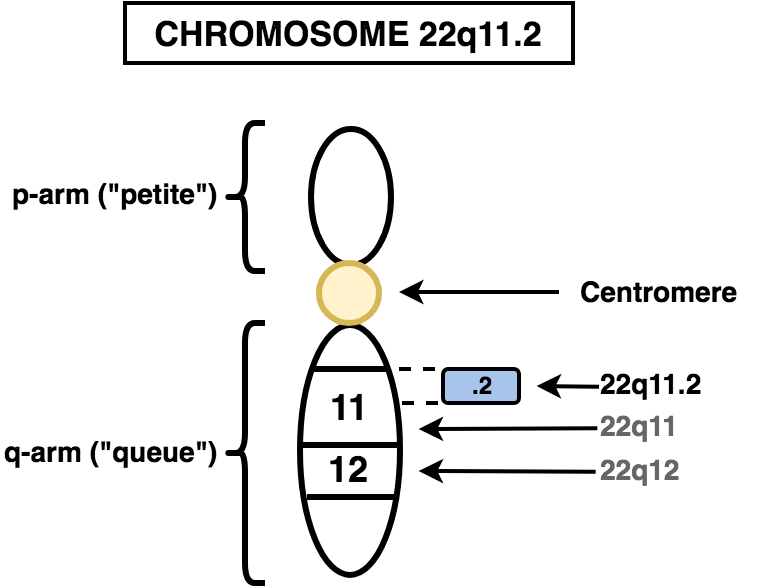

The '22q11.2' in 22q11.2 Deletion Syndrome refers to (see figure 1):- 22: Chromosome 22

- q: the long arm (“queue”) of the chromosome 22

- All chromosomes have a short (“petite” or “p”) arm and a long (“queue” or “q”) arm

- 11.2: the location on chromosome 22 (region (1), band (1), sub-band (2))

Diagnosis

- The diagnosis of DiGeorge Syndrome can be confirmed with various methods of genetic testing, including whole genome array, SNP clinical microarray, comparative genomic hybridization, and Multiplex Ligation-dependent Probe Amplification (MLPA).'

- Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization (FISH) studies can also find the deletion in most patients.

- Cytogenetic (chromosome) testing can also be performed.

Clinical Microarray (CMA)

- The diagnostic yield is around 10-20%. CMA also has limitations in that it will not detect all genetic conditions.

Signs and Symptoms

- Individuals with 22q11 deletion often have hypernasal speech, facial features such as a long and narrow face, narrow palpable fissures, flat cheeks, prominent nose, small ears, small mouth, retruded chin, and heart defects.[4]

Schizophrenia

- The presentation of schizophrenia in individuals with DiGeorge Syndrome is indistinguishable from idiopathic forms of schizophrenia. There is a similar age of onset and prodromal symptoms. Therefore, current guidelines also recommend the same treatment, including with antipsychotics.[5] However, since these patients are at a baseline higher risk of obesity (even without antipsychotic use), there needs to be even more careful monitoring and prevention of metabolic side effects.[6]

- Individuals with DiGeorge syndrome and schizophrenia and typically under-recognized and not diagnosed. The estimated prevalence of schizophrenia patients having DiGeorge, is estimated to be 1 in 100-200 patients.[7]

Antipsychotics Can Mask Early-Onset Parkinson's Symptoms in DiGeorge + Schizophrenia Patients

Individuals with DiGeorge have a higher risk for early-onset Parkinson's Disease.[8] As a result, individuals with concomitant schizophrenia and on long-term antipsychotic treatment may have their emerging Parkinson's symptoms masked and mistakenly attributed as extrapyramidal symptoms.Pathophysiology

- The microdeletion in DiGeorge Syndrome is a new mutation (de novo) in almost 90% of cases.[9] There is a highly variable expression with incomplete penetrance.

Investigations

Bloodwork

Physical Exam

- Congenital heart disease

- Facial dysmorphia and cleft palate

Management and Treatment

- Patients with DiGeorge have complex needs and often require multidisciplinary teams.

Clozapine

- Patients with DiGeorge respond to clozapine treatment as well those with non-DiGeorge schizophrenia.

- However, they may represent an excess of serious adverse events, primarily seizures.[14]

- Lower doses and prophylactic seizure management strategies can help reduce this risk.

- Individuals are also at greater risk for neutropenia and myocarditis.

Supplementation

Resources

For Patients

For Providers

Articles

Research

References

1)

Antshel, K. M., Kates, W. R., Roizen, N., Fremont, W., & Shprintzen, R. J. (2005). 22q11. 2 deletion syndrome: genetics, neuroanatomy and cognitive/behavioral features keywords. Child Neuropsychology, 11(1), 5-19.

2)

Mefford, H. C., Batshaw, M. L., & Hoffman, E. P. (2012). Genomics, intellectual disability, and autism. The New England journal of medicine, 366(8), 733–743.

3)

Miller, D. T., Adam, M. P., Aradhya, S., Biesecker, L. G., Brothman, A. R., Carter, N. P., Church, D. M., Crolla, J. A., Eichler, E. E., Epstein, C. J., Faucett, W. A., Feuk, L., Friedman, J. M., Hamosh, A., Jackson, L., Kaminsky, E. B., Kok, K., Krantz, I. D., Kuhn, R. M., Lee, C., … Ledbetter, D. H. (2010). Consensus statement: chromosomal microarray is a first-tier clinical diagnostic test for individuals with developmental disabilities or congenital anomalies. American journal of human genetics, 86(5), 749–764.

4)

Addington, D., Abidi, S., Garcia-Ortega, I., Honer, W. G., & Ismail, Z. (2017). Canadian guidelines for the assessment and diagnosis of patients with schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorders. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 62(9), 594-603.

5)

Van, L., Boot, E., & Bassett, A. S. (2017). Update on the 22q11. 2 deletion syndrome and its relevance to schizophrenia. Current opinion in psychiatry, 30(3), 191-196.

6)

Voll, S. L., Boot, E., Butcher, N. J., Cooper, S., Heung, T., Chow, E. W., ... & Bassett, A. S. (2017). Obesity in adults with 22q11. 2 deletion syndrome. Genetics in Medicine, 19(2), 204.

7)

Bassett, A. S., Scherer, S. W., & Brzustowicz, L. M. (2010). Copy number variations in schizophrenia: critical review and new perspectives on concepts of genetics and disease. American Journal of Psychiatry, 167(8), 899-914.

8)

Butcher, N. J., Kiehl, T. R., Hazrati, L. N., Chow, E. W., Rogaeva, E., Lang, A. E., & Bassett, A. S. (2013). Association between early-onset Parkinson disease and 22q11. 2 deletion syndrome: identification of a novel genetic form of Parkinson disease and its clinical implications. JAMA neurology, 70(11), 1359-1366.

9)

Fung, W. L. A., Butcher, N. J., Costain, G., Andrade, D. M., Boot, E., Chow, E. W., ... & García-Miñaúr, S. (2015). Practical guidelines for managing adults with 22q11. 2 deletion syndrome. Genetics in Medicine, 17(8), 599.

10)

Fung, W. L. A., Butcher, N. J., Costain, G., Andrade, D. M., Boot, E., Chow, E. W., ... & García-Miñaúr, S. (2015). Practical guidelines for managing adults with 22q11. 2 deletion syndrome. Genetics in Medicine, 17(8), 599.

11)

Fung, W. L. A., Butcher, N. J., Costain, G., Andrade, D. M., Boot, E., Chow, E. W., ... & García-Miñaúr, S. (2015). Practical guidelines for managing adults with 22q11. 2 deletion syndrome. Genetics in Medicine, 17(8), 599.

12)

Bassett, A. S., McDonald-McGinn, D. M., Devriendt, K., Digilio, M. C., Goldenberg, P., Habel, A., ... & Swillen, A. (2011). Practical guidelines for managing patients with 22q11. 2 deletion syndrome. The Journal of pediatrics, 159(2), 332-339.

13)

Fung, W. L. A., Butcher, N. J., Costain, G., Andrade, D. M., Boot, E., Chow, E. W., ... & García-Miñaúr, S. (2015). Practical guidelines for managing adults with 22q11. 2 deletion syndrome. Genetics in Medicine, 17(8), 599.

14)

Butcher, N. J., Fung, W. L. A., Fitzpatrick, L., Guna, A., Andrade, D. M., Lang, A. E., ... & Bassett, A. S. (2015). Response to clozapine in a clinically identifiable subtype of schizophrenia. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 206(6), 484-491.