- Last edited on July 9, 2020

History of the DSM

Primer

The DSM (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders) has a long and storied history in the history of psychiatry. As the cornerstone of psychiatry and guide for millions of clinicians and healthcare providers, it has been the most significant advance in the diagnosis and treatment of mental disorders. However, in the midst of its success, important criticisms of its role have also arisen.

– Allen Frances, MD, Chair of the DSM-IV Task Force

The Cycle of Classification: DSM I through DSM-5

Blashfield, R. K., Keeley, J. W., Flanagan, E. H., & Miles, S. R. (2014). The cycle of classification: DSM-I through DSM-5. Annual review of clinical psychology, 10, 25-51.Pre-DSM Era

DSM-I

DSM-II

Even though the DSM II was published in 1968 (!) the following excerpt is sage advice even (and especially) today.

A Tip From the DSM-II...

The diagnostician, however, should not lose sight of the rule of parsimony and diagnose more conditions than are necessary to account for the clinical picture. The opportunity to make multiple diagnoses does not lessen the physician's responsibility to make a careful differential diagnosis.DSM-III

DSM-IV

DSM-5

Interrater Reliability

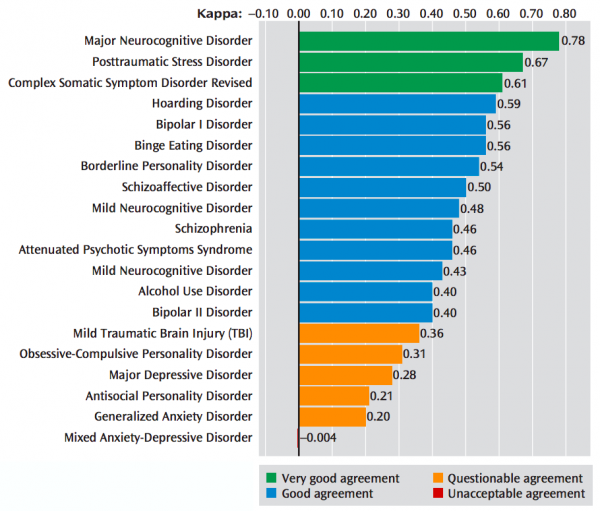

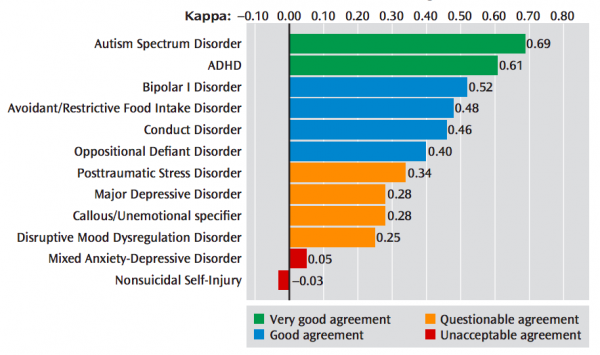

The DSM-5 field trials showed the inherent limitations of the DSM's etiologically agnostic approach to diagnosing mental disorders. Some disorders had good interrater reliability (e.g. - major neurocognitive disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder), while others were very poor. The most prominent example is for major depressive disorder, which has a very poor kappa = 0.28 (questionable agreement). One common reason is because the criteria covers a wide range of illness severity, and is a heterogenous condition.[1]

What is the Kappa Statistic?

Many medical diagnostics (e.g. - physical exams, imaging, and other diagnostic tests) often depend on some subjective interpretation by the observers. This is especially true in psychiatry where there are no objective diagnostics, and the clinician is the the diagnostic tool. Thus, the kappa statistic (or kappa coefficient) is the most commonly used statistic to measure the agreement between two or more observers. A kappa of 1 indicates perfect agreement between observers, whereas a kappa of 0 indicates agreement equivalent to chance. As an example, if an illness appears in 10% of a clinic's patients and two clinicians agree on its diagnosis 85% of the time, the kappa statistic is 0.46 (this is similar to the weighted composite statistic for schizophrenia in this DSM-5 Field Trial).[2][3]Quotes

The DSM-5 on Boundaries Between Disorders

Although some mental disorders may have well-defined boundaries around symptom clusters, scientific evidence now places many, if not most, disorders on a spectrum with closely related disorders that have shared symptoms, shared genetic and environmental risk factors, and possibly shared neural substrates (perhaps most strongly established for a subset of anxiety disorders by neuroimaging and animal models). In short, we have come to recognize that the boundaries between disorders are more porous than originally perceived.– (DSM-5, Introduction, page 5)

The DSM-5 on Checklist Diagnoses

The case formulation for any given patient must involve a careful clinical history and concise summary of the social, psychological, and biological factors that may have contributed to developing a given mental disorder. Hence, it is not sufficient to simply check off the symptoms in the diagnostic criteria to make a mental disorder diagnosis.– (DSM-5, Use of the Manual, page 19)

– Freedman, R., Lewis, D. A., Michels, R., Pine, D. S., Schultz, S. K., Tamminga, C. A., ... & Shrout, P. E. (2013). The initial field trials of DSM-5: new blooms and old thorns.

Readings

ICD-10 and ICD-11

In non-North American circles (i.e. - outside of Canada and the United States), countries use the World Health Organization's International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, also known as the ICD-10.

The diagnostic criteria for the ICD-10 varies from the DSM-5 for a variety of mental disorders. See Tyrer, P. (2014). A comparison of DSM and ICD classifications of mental disorder. Advances in psychiatric treatment, 20(4), 280-285.

Future

Future of Psychiatry

Beyond the Kraepelinian dichotomy

Research Domain Criteria (RDoC)

RDoC is a research framework proposed by the National Institute for Mental Health (NIMH) for new ways of studying mental disorders. It integrates many levels of information (from genomics to self-report) to better understand basic dimensions of functioning underlying the full range of human behaviour from normal to abnormal.

— Allen Frances, DSM-IV Task Force Chairman, 2015

— Thomas Insel, National Institute of Mental Health Director, 2013