- Last edited on April 16, 2024

Conversion Disorder (Functional Neurological Disorder)

Primer

Conversion Disorder (also known as Functional Neurological Symptom Disorder or Functional Neurological Disorder [FND]) is a mental disorder characterized by neurologic symptoms (either motor or sensory) that is incompatible with any known neurologic disease. Common symptoms include weakness and/or paralysis, non-epileptic seizures, movement disorders, speech or visual impairment, swallowing difficulty, sensory disturbances, or cognitive symptoms.

Epidemiology

- The incidence of conversion disorder is estimated to be between 4 to 12 per 100,000 individuals annually.

- About 30% of new patients seen in neurology clinics have symptoms that are either not at all or only partly explained by structural neurologic disease.

Prognosis

- Onset tends to be in middle age between ages 35 to 50 years old.

Comorbidity

- About 25% do have a comorbid neurological disorder.

Risk Factors

- About 37% of individuals with conversion disorder have had a physical injury preceding symptom onset.[1]

History

Terminology

Many clinicians use the alternative names of “functional” (referring to abnormal central nervous system functioning) or “psychogenic” (referring to a “psychiatric” etiology) to describe the symptoms of conversion disorder.

DSM-5 Diagnostic Criteria

Criterion A

1 or more symptoms of altered voluntary motor or sensory function.

Criterion A!

Criterion B

Clinical findings provide evidence of incompatibility between the symptom and recognized neurological or medical conditions.

Criterion C

The symptom or deficit is not better explained by another medical or mental disorder.

Criterion D

The symptom or deficit causes clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning or warrants medical evaluation.

Specifiers

Symptom Type Specifiers

Specify symptom type:

- With weakness or paralysis

- With abnormal movement (e.g. - tremor, dystonic movement, myoclonus, gait disorder)

- With swallowing symptoms

- With speech symptom (e.g. - aphasia, dysphonia, slurred speech)

- With seizure attacks or seizures

- With anesthesia or sensory loss

- With special sensory symptom (e.g. - visual, olfactory, or hearing disturbance such as tinnitus)

- With mixed symptoms

Episode and Stressor Specifier

Specify if:

- Acute episode: Symptoms present for less than

6months. - Persistent: Symptoms occurring for

6months or more.

Specify if:

- With psychological stressor (specify stressor)

- Without psychological stressor

Signs and Symptoms

- Conversion disorder involves either neurologically-incomptabile sensory or motor symptoms, but note that pain is not a part of the diagnostic criteria for conversion disorder!

- The diagnosis of functional neurological disorder is made through identification of positive symptoms (e.g. - symptoms resolve with distractibility) rather than as a diagnosis of exclusion.

- In conversion disorder, when an individual is distracted, there is usually a reduction or even disappearance of the movement disorder

Screening Tools and Scales

Pathophysiology

- Historically, the psychological causation model of functional disorders suggests that these disorders occur when psychological or psychiatric distress is non-consciously and involuntarily expressed as physical symptoms and signs.[2]

Differential Diagnosis

- Another mental disorder

- If another mental disorder better explains the symptoms, that diagnosis should be made. However the diagnosis of conversion disorder may be made in the presence of another mental disorder.

- Neurological disease

- The main differential diagnosis is neurological disease that might better explain the symptoms. After a thorough neurological assessment, an unexpected neurological disease cause for the symptoms is rarely found at follow up. However, reassessment may be required if the symptoms appear to be progressive. Conversion disorder may coexist with neurological disease.

-

- Conversion disorder may be diagnosed in addition to somatic symptom disorder. Most of the somatic symptoms encountered in somatic symptom disorder cannot be demonstrated to be clearly incompatible with pathophysiology (e.g., pain, fatigue), whereas in conversion disorder, such incompatibility is required for the diagnosis. The excessive thoughts, feelings, and behaviours characterizing somatic symptom disorder are often absent in conversion disorder.

-

- The diagnosis of conversion disorder does not require the judgment that the symptoms are not intentionally produced (i.e. - not feigned), because assessment of conscious intention is unreliable. However definite evidence of feigning (e.g. - clear evidence that loss of function is present during the examination but not at home) would suggest a diagnosis of factitious disorder if the individual's apparent aim is to assume the sick role or malingering if the aim is to obtain an incentive such as money.

-

- Dissociative symptoms are common in individuals with conversion disorder. If both conversion disorder and a dissociative disorder are present, both diagnoses should be made.

-

- Individuals with body dysmorphic disorder are excessively concerned about a perceived defect in their physical features but do not complain of symptoms of sensory or motor functioning in the affected body part.

-

- In depressive disorders, individuals may report general heaviness of their limbs, whereas the weakness of conversion disorder is more focal and prominent. Depressive disorders are also differentiated by the presence of core depressive symptoms.

-

- Episodic neurological symptoms (e.g., tremors and paresthesias) can occur in both conversion disorder and panic attacks. In panic attacks, the neurological symptoms are typically transient and acutely episodic with characteristic cardiorespiratory symptoms. Loss of awareness with amnesia for the attack and violent limb movements occur in non-epileptic attacks, but not in panic attacks.

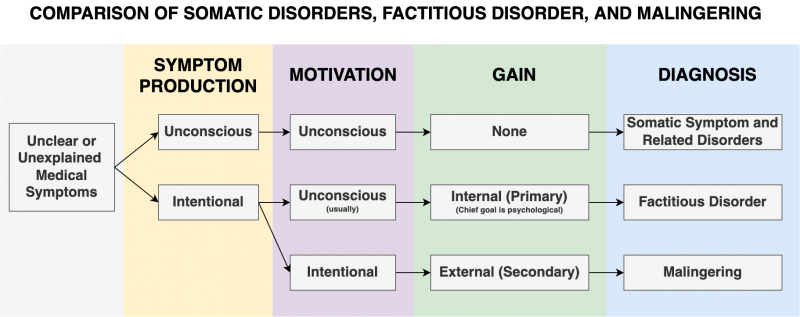

Comparison of Somatic Disorders

Investigations

Physical Exam

Don't Base the Diagnosis on Just One Finding!

The diagnosis of conversion disorder should be based on the overall clinical picture and not on a single clinical finding.- Hoover's sign

- Weakness of hip extension returns to normal strength with contralateral hip flexion against resistance.

- Weakness

- Marked weakness of ankle plantar-flexion when tested on the bed in an individual who is able to walk on tiptoes

- Tremor entrainment test

- A unilateral tremor may be functional if the tremor changes when the individual is distracted away from it. This may be observed if the individual is asked to copy the examiner in making a rhythmical movement with their unaffected hand and this causes the functional tremor to change such that it copies or “entrains” to the rhythm of the unaffected hand or the functional tremor is suppressed, or no longer makes a simple rhythmical movement.

- Seizures

- The drop-arm test can be helpful as clinical clue[4]

- In attacks resembling epilepsy or syncope (“psychogenic” non-epileptic attacks), the occurrence of closed eyes with resistance to opening or a normal simultaneous electroencephalogram (although this alone does not exclude all forms of epilepsy or syncope)

- Pupillary and gag reflexes retained post-pseudoseizure

- Visual blindness

- A tubular visual field (i.e. - tunnel vision) may indicate conversion

- In patients reporting severe monocular or binocular limitations, normal visual evoked potential (VEP) results plus a normal neuro-ophthalmic examination is strongly suggestive of functional origin.[5]

- Normal pupillary reflexes and preserved optokinetic nystagmus suggest grossly intact subcortical and cortical visual pathways and therefore a functional

- Electrophysiological testing and structural neuroimaging is often needed to confirm the diagnosis of functional blindness, so as to rule out cortical pathology, including cortical blindness.

Functional Tremors

Treatment

Education

- Education and self-help techniques is the most important first-line treatment.[6]

- Summarize the symptom and signs from which the patient is suffering, at length if necessary, and integrate an understanding of the course of the illness into that review.

- Describe the steps that have been taken to exclude pathological causes of the symptoms.

- Review the different structures and systems that could be malfunctioning to cause such symptoms, and describe the ways in which general medical causes for the symptoms have been excluded.

- This possibility of diagnostic error (i.e., the diagnosis of a functional disorder) should also be shared with the patient, and, most important, should be weighed against the risk of not treating a potentially treatable disorder.

- Remind the patient that conversion disorder is a treatable condition, and that it is a disorder of function (i.e. - “software”) rather than structure (i.e. - “hardware”). There is limited role for medications in conversion disorder.

- The emphasis is that the illness involves brain function rather than brain structure

- It is important to tell the patient the mechanisms are unconscious and involuntary, and they are not malingering

Psychotherapy

- Cognitive behavioural therapy has good second-line evidence.[7]

Physical Therapy

- Physical therapy is recommended for motor symptoms of conversion disorder. Having a gradual and graded approach is helpful. Remind the patient to take time to give themselves a chance to recover.

Pharmacotherapy

- Haloperidol and sulpiride have been studied in conversion disorder.[8]

- ECT for patients with psychogenic nonepileptic seizures may provide benefit.[9]

Negative Prognostic Factors

- Negative prognostic factors include:

- Inability to notice variability in symptoms or positive signs of FND when shown

- Low personal agency or help-seeking/rejecting style

- Multi-systemic symptoms as opposed to single symptom presentation

- Chronicity of symptoms and poor coping (i.e., patient is destabilized by a new illness model)

- Active litigation is strong perpetuating factor for symptoms