- Last edited on July 20, 2024

Lithium

Primer

Lithium is an alkalai metal and mood stabilizer used in the treatment of all phases (manic, maintenance, and depressive) of bipolar I disorder. It is the gold standard treatment for bipolar I disorder and mania.

Pharmacokinetics

See also article: Introduction to Pharmacology

Pharmacokinetics of Lithium

| Absorption | Lithium is rapidly absorbed from the GI tract, with Tmax= 1-3 hours (adults). With extended-release tablets (Lithmax SR), absorption is delayed, with Tmax=4-12 hours (adults). Food or antacids do not appear to influence absorption. |

|---|---|

| Distribution | Lithium is not protein bound, and distributes freely throughout body water, both intra- and extracellularly |

| Metabolism | Lithium is not metabolized, rather, it is excreted almost entirely by the kidneys (95%). |

| Elimination | Lithium is excreted almost exclusively excreted by the kidneys; most lithium is reabsorbed at the proximal convoluted tubules via sodium channels. |

| Half-life | 18-36 hours |

See also article: Cytochrome (CYP) P450 Metabolism

Lithium: Cytochrome P450 Metabolism

| Substrate of (Metabolized by) | Not applicable |

|---|---|

| Induces | - |

| Inhibits | - |

Pharmacodynamics

Mechanism of Action

- Since sodium is so pervasive in the human body and lithium can also alter these processes, it has been very difficult to identify the key mechanism of action of lithium in regulating mood.

- For example, there is some evidence that people with bipolar illness have higher intracellular concentrations of sodium and calcium than controls, and that lithium can reduce these.

- Lithium is hypothesized to modulate dopaminergic, glutamatergic and gabaergic neurotransmission.[1] Lithium alters sodium transport across the cell membranes of nerve and muscle cells. There are multiple proposed mechanisms for lithium in its role in treatment of mania and bipolar disorder, including:

- Inhibition of inositol monophosphatase intracellular signaling

- Altering metabolism of neurotransmitters including catecholamines and serotonin

- Effects neural plasticity through effects on glycogen synthetase kinase-3β , cyclic AMP- dependent kinase, protein kinase C

- Increasing cytoprotective proteins

- Activating signaling cascade used by endogenous growth factors

- Potentially inducing neurogenesis at synaptic sites.

- Subsequent actions by lithium include:

- Increasing synthesis of serotonin by increasing tryptophan reuptake in synaptic terminals

- Downregulation of 5-HT1A, 5-HT1B, 5-HT2 receptors

- Increasing rate of synthesis of norepinephrine

- During manic episodes, lithium is thought to reduce the excretion of norepinephrine

- During manic episodes, lithium is thought to increase excretion of norepinephrine metabolites

Toxicity and Overdose

Most risk factors for developing lithium toxicity involve changes in sodium levels or the way the patient's body handles sodium. For example low salt diets, dehydration, drug-drug interactions (see below) and illnesses like Addison’s disease can lead to toxicity. Patients should be well-informed of these risk factors when starting treatment. Also, always remember to treat the patient and not the number! Serum lithium concentrations do not always reliably correlate with the clinical severity of toxicity.[2]

Toxic Lithium Levels

| Level (mmol/L) | Symptoms |

|---|---|

| >1.5 | • GI symptoms (anorexia, nausea and diarrhea) • CNS symptoms (muscle weakness, drowsiness, ataxia, coarse tremor and muscle twitching). |

| >2.0 | • Blurred vision, confusion, slurred speech, unsteady gait. • Increased disorientation and seizures usually occur, which can progress to coma, and ultimately death. • Osmotic or alkaline diuresis can be used (not thiazide or loop diuretics, which would worsen symptoms!) |

| >3.0 | • Severe toxicity, coma, cardiovascular collapse, death. • Peritoneal or hemodialysis is often used for emergency management. |

Indications

-

- Lithium is effective in the treatment of moderate to severe mania (NNT = 6), and for prophylaxis of bipolar affective disorder (reduces both the number and the severity of relapses, NNT = 10-14).[3]

- Lithium is more effective at preventing manic than depressive relapse. Lithium also offers some protection against antidepressant‐induced hypomania.

- It is generally clinically appropriate to initiate prophylactic treatment after a single manic episode that was associated with significant risk and adverse consequences, or in bipolar I illness, two or more acute episodes.

- Major depressive disorder, most commonly as an adjunctive medication

Dosing and Target Level

Dosing for Lithium

| Starting | • Outpatient: 300 mg PO daily for the first week • Inpatient: 600 mg PO daily for the first week and generally titrated more aggressively |

|---|---|

| Titration | Increments of 300 to 600 mg each week during the titration phase |

| Maximum | Typically does not exceed 2400 mg per day (though the lithium level is most important) |

| Taper | See below |

Lithium Levels

| Level (mmol/L) | |

|---|---|

| Maintenance/prophylaxis | 0.6 to 1.0 |

| Acute bipolar mania/depression (<65 years) | 0.8 to 1.2* |

| Acute bipolar mania/depression (>65 years) | 0.4 to 0.8 |

| Toxic levels | > 1.5 mmol/L |

- It is the lithium plasma level (not the lithium dose) that is clinically significant.

- Keep in mind that rapid increases will lead to more GI side effects.

- Children and adolescents may require higher plasma levels than adults due to differences in drug distribution and pharmacokinetics. The optimal plasma level ranges for lithium used unipolar depression are less clear, and typically do not need to reach the levels used in bipolar disorder.

- Once daily dosing can reduce the severity of side effects of lithium.[4]

- Dosing it at night can also be helpful because lithium can be sedating for some patients. Patients should be reminded to drink more water to ensure hydration, and to also reduce their salt intake.

Calculating the target dose

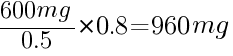

To calculate how much to increase a dose by, take the current dose the patient is at, and divide it over the current lithium level. For example, if your patient is taking 600mg per day, and their most recent lithium level is 0.5 (i.e. - subtherapeutic), and you want to reach a level of 0.8, you would do the following calculation:

960mg would be the next dose to give to your patient to reach the target dose of 0.8. You would need to wait another 5 half-lives before measuring the trough levels again.

Formulations

- Lithium comes in oral and liquid formulation.

Monitoring

What Time Should the Bloodwork Be Done?

Lithium is rapidly absorbed from the gastrointestinal tract but has a long distribution phase. Plasma lithium levels should be taken 10–14 hours (ideally 12 hours) after the last dose. Therefore, your patients should not be taking lithium the morning of the bloodwork! They can take their dose again after their blood work.Lithium Monitoring

| Stage of treatment | Everyone | High Risk/Geriatric |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-treatment | Cr (eGFR), BUN, TSH, total calcium, albumin, weight, height, blood pressure | ECG (cardiovascular risks or dysfunction), fasting glucose, lipid panel |

| Starting | • Plasma lithium level 7 days after starting treatment (you are measuring the trough level, i.e. - 12 hours after last dose, [though there is some debate on this[5][6][7]] • Measure plasma lithium after another 7 days, and titrate dose as needed. • This q1-2 weekly monitoring should continue until you have 2 consecutive levels within the therapeutic range (0.8 to 1.2) for the same dosage | Start with a lower dose of lithium, with similar monitoring |

| Ongoing | • Plasma lithium level, electrolytes, Cr (eGFR), TSH, BUN, q6-12 months. • Serum calcium, albumin, q1 year • Parathyroid hormone levels should be measured in patients with elevated calcium levels | Elderly, those with drug-drug interactions, existing renal impairment, or other illnesses should be monitored more closely. |

| Stopping | Dose needs to be reduced slowly over the course of 1 month. Reductions in plasma level should not be > 0.2mmol/L each time you reduce the dose. | |

Tapering or Discontinuation

Never Discontinue Lithium Abruptly!

Discontinuing lithium abruptly or in less than 2 weeks, rather than tapering (> 2 weeks) doubles the risk of a recurrent mood episode in 1 year; and the risk increases by 20 times in 3 years. At least 1 month should be spent tapering off lithium.[8] Abrupt discontinuation of lithium and may actually exceed that of the risk of the untreated disorder.[9][10][11] The reason for this “rebound effect” remains (unfortunately) a poorly understood mechanism.- Some recommendations have been made that lithium treatment should not be started unless there is a clear intention to continue it for at least 3 years.[14]

- This advice has obvious implications for initiating lithium treatment against a patient’s will (or in a patient known to be non‐adherent with medication) during a period of acute illness.

Sodium Intake

- Sodium balance (i.e. - salt intake) can have an impact on lithium levels. When there is sodium depletion (i.e. - hyponatremia or low sodium intake), lithium undergoes higher reabsorption, resulting in higher serum levels. Conversely, when there is high sodium intake, there is decreased lithium reabsorption, resulting in lower serum levels.

Benefits

Neuroprotection

- Increasingly, some observational and retrospective studies have shown a lower risk for dementia in individuals with mood disorders treated with lithium.[17]

Suicide Prevention

- Lithium is one of two psychotropics (the other is clozapine) that has evidence that it reduces the risk of suicide.[18][19][20]

- The mechanism of this is still under investigation, but theories focus largely on its effects on neurotransmitters.

- The most common hypothesis is that lithium leads to a decrease in impulsivity and aggression via several influences within the nerve cell.[23]

- Another study showed that the use of lithium as an augmentation agent (i.e. - in addition to a primary medication) at sub-therapeutic doses (<0.54) did not reduce the overall incidence of suicide-related events compared to placebo.[26]

Contraindications

Absolute

- Lithium should not be used during first trimester of pregnancy, due to increased risk for Ebstein's anomaly (cardiac malformation)

- Although traditionally considered an absolute contraindication, there is some argument from certain clinicians that the risks and benefits should be discussed with the individual patient (e.g. - high risk for relapse or severe deterioration when off lithium).[27]

- Severe renal impairment

- Cardiovascular disease with arrythmias (can cause reversible T-wave changes, or unmask Brugada syndrome)

- Addison's disease

- Untreated hypothyroidism or thyroid disorder

Relative

- Mild renal disease

Drug-Drug Interactions

Common Drug-Drug Interactions

Adapted from: Taylor, D. M. et al. (2018). The Maudsley prescribing guidelines in psychiatry. John Wiley and Sons.| Drug | Examples | Interaction |

|---|---|---|

| ACE Inhibitors | Captopril, cilazapril enalapril, fosinopril, imidapril, lisinopril, moexipril, perindopril, quinapril, ramipril and trandolapril | Reduces thirst which can lead to mild dehydration. Increases renal sodium loss leading to increased sodium re‐absorption by the kidney, resulting in an increase in lithium plasma levels. In the elderly, ACE inhibitors increase seven‐fold the risk of hospitalisation due to lithium toxicity. ACE inhibitors can also precipitate renal failure so, if co‐prescribed with lithium, more frequent monitoring of e‐GFR and plasma lithium is required. |

| Angiotensin II Receptor Antagonists (ARBs) | Candesartan, eprosartan, irbesartan, losartan, olmesartan, telmisartan and valsartan | Similar drug-drug interactions as with ACE inhibitors. |

| Thiazide and Loop Diuretics | Thiazide diuretics: bendroflumethiazide, chlortalidone, cyclopenthiazide, indapamide, metolazone and xipamide Loop diuretics: bumetanide, furosemide and torasemide | Diuretics reduces the renal clearance of lithium. Thiazide diuretics have a much larger effect compared to loop diuretics. Lithium levels usually rise within 10 days of a thiazide diuretic being prescribed; the magnitude of the rise is unpredictable and can vary from an increase of 25% to 400%. Although there are case reports of lithium toxicity induced by loop diuretics, many patients can recieve this combination of drugs without apparent problems. |

| NSAIDs / COX-2 Inhibitors | Aceclofenac, acemetacin, celecoxib, dexibuprofen, dexketofrofen, diclofenac, diflunisal, etodolac, etoricoxib, fenbufen, fenoprofen, flurbiprofen, ibuprofen, indometacin, ketoprofen, lumiracoxib, mefenamic acid, meloxicam, nabumetone, naproxen, piroxicam, sulindac, tenoxicam and tiaprofenic acid | NSAIDs inhibit the synthesis of renal prostaglandins, reducing renal blood flow, which increases renal re‐absorption of sodium and therefore lithium. The magnitude of the rise is unpredictable for any given patient; case reports vary from increases of around 10% to over 400%. |

Side Effects

Common

- Side effects with lithium are dose-related. Therefore, knowing the plasma level of lithium allows you to gauge the degree of side effects that a patient might encounter. If a patient isn't experiencing any side effects at all (even minor ones), it should already tell you that they are likely on a very subtherapeutic dose of lithium.

- The most common side effects of lithium include: metallic taste in the mouth, gastro‐intestinal upset such as diarrhea, fine tremors, polyuria and polydipsia (polyuria may occur more frequently with BID dosing), ankle edema, and weight gain.

Mnemonic

The mnemonicLMNOP can be used to remember important side effects and adverse events related to lithium:L- LithiumM- Movement (tremor)N- Nephrology (kidney injury) and nephrogenic diabetes insipidus (thirst and urination)O- HypOthyroidismP- Pregnancy (Ebstein's anomaly)

Tremor

See main article: Approach to Tremors

- Lithium tremors are classified as a postural tremor and produced by voluntary maintenance of a particular posture held against gravity typically at a frequency of 8 to 12 Hz in the hands.[28]

- The prevalence of lithium tremors varies widely depending on the study, ranging from 4% to 65% (average 27%).[29]

- For most patients a lithium tremor is tolerable and does improve spontaneously over time.

- Lithium tremors can be both non-toxic (i.e. - from chronic lithium use), and toxic (i.e. - a sign of acute intoxication)

- Tremors that begin at the start or during titration of lithium treatment usually suggests lithium tremor. Serum lithium concentration should always be checked during these periods to rule out lithium toxicity.

- Lithium tremors can be managed with beta blockers (e.g. - propranolol), primidone, gabapentin, and topiramate. Benzodiazepines are not generally recommended due to the risk for falls, dependence, and cognitive impairment.

Dermatological

- Psoriasis, acne, alopecia can also occur (hair often regrows with or without stopping lithium).

Nephrogenic Diabetes Insipidus

- Nephrogenic diabetes insipidus (NDI) is characterized by intense thirst and polyuria with inability to concentrate urine due to a reduction of ADH (antidiuretic hormone, also known as vasopressin). Chronic lithium use can cause ADH resistance in the kidneys, leading to decreased urinary concentrating capacity. NDI is usually reversible in the short to medium term but may be irreversible after long‐term treatment with lithium (i.e. - over 15 years).

- Lithium levels that are >0.8 mmol/L are associated with a higher risk of nephrotoxicity. NDI can be diagnosed with a water restriction test, and considered positive when there is no change in urine osmolality despite restriction.

- Management includes discontinuing lithium, reducing the daily dosage, or reducing the dosing schedule. Diuretics can also be used to treat NDI, but requires close monitoring of lithium and potassium levels.[30]

Hypothyroidism

See main article: Hypothyroidism

- Long-term lithium use increases the risk of hypothyroidism. In middle‐aged women, the risk may be up to 20%, while up to 30% develop asymptomatic elevated TSH. Lithium-related hypothyroidism can be easily treated with levothyroxine.

- Some clinicians suggest testing for thyroid autoantibodies in middle-aged women before starting lithium (to better estimate the risk of hypothyroidism) and for monitoring more frequently in the first year of treatment.[31]

Hypercalcemia and Hyperparathyroidism

See main article: Hypercalcemia and Hyperparathyroidism

- These two conditions are frequently under-diagnosed in psychiatric practice and there are recommendations that calcium levels should be monitored in patients on long‐term treatment.[34] Sequelae of long-term chronic hypercalcemia includes renal stones, osteoporosis, dyspepsia, hypertension and renal impairment.

- Symptoms of hypercalcemia (and consequently hyperparathyroidism) can also mimic as psychiatric disorders, with disturbances of mood, energy, and cognition.

Leukocytosis and Neutrophilia

- Lithium can cause leukocytosis, neutrophilia, and increased platelet counts.[35]

Cardiac (ECG)

See main article: QT (QTc) Prolongation and Monitoring

- Lithium can cause changes on ECG, including QTc prolongation, T-wave flattening or inversion, bradycardia, sick sinus node syndrome, and AV block.

Adverse Events

Teratogen

Lithium is a Human Teratogen!

Lithium is associated with cardiac malformations (in particular, Ebstein's anomaly) and increased birth weight.[36] Every woman of child‐bearing age on lithium should be advised to use a reliable form of contraception.Nephrotoxicity

- Long-term use of lithium (i.e. - over decades) has been linked to chronic kidney disease (CKD) and end-stage renal disease (ESRD). The estimated risk of developing CKD and progressing to ESRD is around 1.5% in long-term lithium users.[37] Importantly, the majority of patients on long-term lithium treatment do not appear to develop impaired renal function.[38]

- More recent studies have found that the trajectory of kidney function decline varies widely between individuals on lithium long-term. In patients with a fast trajectory, a trade-off is required between continuing lithium to treat mental health problems and discontinuing lithium for the sake of renal health.[39]

- On a population level, cohort studies show that lithium use is associated with an additional eGFR deterioration of 0.54mL/min/1·73m² per year.[40]

- Routine monitoring for both creatinine and eGFR is thus important for patient on lithium. There are no strict eGFR cut-offs for discontinuing lithium if there is concern about nephrotoxicity (CKD is defined as eGFR <60mL/min). Guidelines suggest referring to nephrology if:[41]

- eGFR falls by >5 mL/min in 1 year, or >10 mL/min within 5 years, or

- eGFR <45mL/min in two consecutive readings, or

- Clinician is concerned for other reasons

Clinical Pearls

- Interestingly, drinking caffeine can reduce lithium levels, as it is thought to increase renal lithium clearance.[42]

Special Populations

Geriatric

See main article: Geriatric Pharmacology

- For geriatric patients, lithium levels should be <0.8 mmol/L where possible (0.4 to 0.6 for depression, and 0.4 to 0.8 for mania/hypomania). Once daily dosing is best, and it is best to start at a lower dose of 150 mg per day.

- Typically, 450 mg per day is enough to reach a therapeutic level for geriatric patients. In some cases, a therapeutic effect is achieved between 0.2 to 0.6 mmol/L, this is because there is a lower correlation between serum lithium levels and cerebrospinal levels in older age (due to a leakier blood brain barrier).

- Make sure that chronic conditions like diabetes, hypertension, and cardiovascular risk factors are well-controlled. The medical risks and benefits of lithium needs to be carefully weighted in older users of lithium, particularly when chronic kidney disease is more common in this population. Lithium overall remains an under-utilized treatment in this population despite overwhelming evidence for it use, its possible neuroprotective effects, and decreased mortality rates.

Pediatric

See main article: Pediatric Pharmacology

Obstetric and Fetal

See main article: Obstetric and Fetal Pharmacology

- Lithium should be held 24 hours prior to delivery due to risks of massive fluid shifts from delivery causing lithium toxicity

- For pregnancy women on lithium, post-delivery, it is essential to monitor the infant for signs of hypotonia and “floppy baby syndrome” in the first 48 hours.

- Breastfeeding is also not recommended as lithium is expressed in the breast milk

Medically Ill

See main article: Psychotropic Dosing in the Medically Ill

- Lithium levels and renal function should be closely monitored in those with renal disease.

Resources

For Providers

Research/Case Reports

References

2)

Kobylianskii, J., Austin, E., Gold, W. L., & Wu, P. E. (2021). A 54-year-old woman with chronic lithium toxicity. CMAJ, 193(34), E1345-E1348.

3)

Taylor, David. Chapter 3, Bipolar Disorders. The Maudsley Prescribing Guidelines in Psychiatry, Twelfth Edition. pg. 189

4)

Girardi, P., Brugnoli, R., Manfredi, G., & Sani, G. (2016). Lithium in bipolar disorder: optimizing therapy using prolonged-release formulations. Drugs in R&D, 1-10.

5)

Reddy, D. S., & Reddy, M. S. (2014). Serum lithium levels: ideal time for sample collection! Are we doing it right?. Indian Journal of Psychological Medicine, 36(3), 346-347.

6)

Black KJ. Optimal timing for lithium levels [version 1; peer review: 1 approved with reservations]. F1000Research 2022, 11:779

7)

Nolen, W. A., Licht, R. W., Young, A. H., Malhi, G. S., Tohen, M., Vieta, E., ... & ISBD/IGSLI Task Force on the treatment with lithium. (2019). What is the optimal serum level for lithium in the maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder? A systematic review and recommendations from the ISBD/IGSLI Task Force on treatment with lithium. Bipolar disorders, 21(5), 394-409.

8)

Baldessarini, R. J., Tondo, L., Faedda, G. L., Suppes, T. R., Floris, G., & Rudas, N. (1996). Effects of the rate of discontinuing lithium maintenance treatment in bipolar disorders. The Journal of clinical psychiatry, 57(10), 441-448.

9)

Suppes, T., Baldessarini, R. J., Faedda, G. L., & Tohen, M. (1991). Risk of recurrence following discontinuation of lithium treatment in bipolar disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry, 48(12), 1082-1088.

10)

Suppes, T., Baldessarini, R. J., Faedda, G. L., & Tohen, M. (1991). Risk of recurrence following discontinuation of lithium treatment in bipolar disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry, 48(12), 1082-1088.

11)

MacQueen, G., & Joffe, R. T. (2004). The clinical effects of lithium discontinuation: The debate continues.

12)

Cavanagh J et al. Relapse into mania or depression following lithium discontinuation: a 7‐year follow‐up. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2004;109:91–95.

13)

Yazici O et al. Controlled lithium discontinuation in bipolar patients with good response to long‐term lithium prophylaxis. J Affect Disord 2004; 80:269–271.

14)

Goodwin GM. Recurrence of mania after lithium withdrawal. Implications for the use of lithium in the treatment of bipolar affective disorder. Br J Psychiatry 1994; 164:149–152.

15)

Marmol, F. (2008). Lithium: bipolar disorder and neurodegenerative diseases Possible cellular mechanisms of the therapeutic effects of lithium. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry, 32(8), 1761-1771.

16)

Taylor, David. Chapter 3, Bipolar Disorders. The Maudsley Prescribing Guidelines in Psychiatry, Twelfth Edition. pg 190.

17)

Diniz, B. S., Machado-Vieira, R., & Forlenza, O. V. (2013). Lithium and neuroprotection: translational evidence and implications for the treatment of neuropsychiatric disorders. Neuropsychiatric disease and treatment, 9, 493.

18)

Lewitzka U, Severus E, Bauer R, Ritter P, Müller-Oerlinghausen B, Bauer M. The suicide prevention effect of lithium: more than 20 years of evidence—a narrative review. International Journal of Bipolar Disorders. 2015;3:15

19)

Fitzgerald, C., Christensen, R. H. B., Simons, J., Andersen, P. K., Benros, M. E., Nordentoft, M., ... & Hawton, K. (2022). Effectiveness of medical treatment for bipolar disorder regarding suicide, self-harm and psychiatric hospital admission: between-and within-individual study on Danish national data. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 1-9.

20)

Cipriani, A., Hawton, K., Stockton, S., & Geddes, J. R. (2013). Lithium in the prevention of suicide in mood disorders: updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Bmj, 346.

21)

Sarai, S. K., Mekala, H. M., & Lippmann, S. (2018). Lithium suicide prevention: a brief review and reminder. Innovations in clinical neuroscience, 15(11-12), 30.

22)

Lewitzka, U., Severus, E., Bauer, R., Ritter, P., Müller-Oerlinghausen, B., & Bauer, M. (2015). The suicide prevention effect of lithium: more than 20 years of evidence—a narrative review. International journal of bipolar disorders, 3(1), 1-16.

23)

Müller-Oerlinghausen, Bruno, and Ute Lewitzka. "Lithium reduces pathological aggression and suicidality: a mini-review." Neuropsychobiology 62.1 (2010): 43-49.

24)

Nabi, Z., Stansfeld, J., Plöderl, M., Wood, L., & Moncrieff, J. (2022). Effects of lithium on suicide and suicidal behaviour: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised trials. Epidemiology and psychiatric sciences, 31, e65.

26)

Katz, I. R., Rogers, M. P., Lew, R., Thwin, S. S., Doros, G., Ahearn, E., ... & Li+ plus Investigators. (2021). Lithium treatment in the prevention of repeat suicide-related outcomes in veterans with major depression or bipolar disorder: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA psychiatry.

27)

Poels, E. M., Bijma, H. H., Galbally, M., & Bergink, V. (2018). Lithium during pregnancy and after delivery: a review. International journal of bipolar disorders, 6(1), 1-12.

28)

Baek, J. H., Kinrys, G., & Nierenberg, A. A. (2014). Lithium tremor revisited: pathophysiology and treatment. Acta psychiatrica scandinavica, 129(1), 17-23.

29)

Baek, J. H., Kinrys, G., & Nierenberg, A. A. (2014). Lithium tremor revisited: pathophysiology and treatment. Acta psychiatrica scandinavica, 129(1), 17-23.

30)

Andreasen, A., & Ellingrod, V. L. (2013). Lithium-induced diabetes insipidus: prevention and management. Current Psychiatry, 12(7), 42.

31)

Bocchetta, A., & Loviselli, A. (2006). Lithium treatment and thyroid abnormalities. Clinical Practice and Epidemiology in Mental Health, 2(1), 23.

32)

Lehmann, S. W., & Lee, J. (2013). Lithium-associated hypercalcemia and hyperparathyroidism in the elderly: What do we know?. Journal of affective disorders, 146(2), 151-157.

33)

Lehmann, S. W., & Lee, J. (2013). Lithium-associated hypercalcemia and hyperparathyroidism in the elderly: What do we know?. Journal of affective disorders, 146(2), 151-157.

34)

Shapiro, H. I., & Davis, K. A. (2014). Hypercalcemia and “primary” hyperparathyroidism during lithium therapy. American Journal of Psychiatry, 172(1), 12-15.

35)

Kast, R. E. (2008). How lithium treatment generates neutrophilia by enhancing phosphorylation of GSK-3, increasing HIF-1 levels and how this path is important during engraftment. Bone marrow transplantation, 41(1), 23.

36)

Cohen, L. S., Friedman, J. M., Jefferson, J. W., Johnson, E. M., & Weiner, M. L. (1994). A reevaluation of risk of in utero exposure to lithium. Jama, 271(2), 146-150.

37)

Gitlin, M. (2016). Lithium side effects and toxicity: prevalence and management strategies. International journal of bipolar disorders, 4(1), 1-10.

38)

Ng, F., Mammen, O. K., Wilting, I., Sachs, G. S., Ferrier, I. N., Cassidy, F., ... & Berk, M. (2009). The International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) consensus guidelines for the safety monitoring of bipolar disorder treatments. Bipolar disorders, 11(6), 559-595.

39)

Strawbridge, R., & Young, A. H. (2022). Lithium: balancing mental and renal health. The Lancet Psychiatry, 9(10), 760-761.

40)

Fransson, F., Werneke, U., Harju, V., Öhlund, L., de Man Lapidoth, J., Jonsson, P. A., ... & Ott, M. (2022). Kidney function in patients with bipolar disorder with and without lithium treatment compared with the general population in northern Sweden: results from the LiSIE and MONICA cohorts. The Lancet Psychiatry, 9(10), 804-814.

41)

Yatham, L. N., Kennedy, S. H., Parikh, S. V., Schaffer, A., Bond, D. J., Frey, B. N., ... & Alda, M. (2018). Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) and International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) 2018 guidelines for the management of patients with bipolar disorder. Bipolar disorders, 20(2), 97-170.