- Last edited on January 11, 2024

Introduction to Antidepressants

Primer

Antidepressants are a class of medications used primarily in the treatment of mood disorders (e.g. - major depressive disorder) and anxiety disorders. Its use has expanded to neurodegenerative and neuropsychiatric disorders in recent years.

History

- The development and history of antidepressants began in the 1950s, with the clinical use of two antidepressant drugs: iproniazid (a monoamine-oxidase inhibitor, or MAOI) and imipramine (a tricyclic antidepressant, or TCA).[1]

- Iproniazid was used to treat tuberculosis at the time, but it was noticed that it also significantly improved the mood of patients, beyond just treating the medical illness. Imipramine, on the other hand, was discovered through a series of trials and errors by experimentation by Swiss psychiatrist Roland Kuhn.[2][3]

- These two discoveries heralded the first step towards psychopharmacology, as the only other major treatment that was available at the time was electroconvulsive therapy. The efficacy of these medications led to various theories on why the medications worked, including the monoamine hypothesis.

- TCAs and MAOIs remained the mainstay of antidepressant treatment until the introduction of fluoxetine, a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI), in the late 1980s.[4]

The SSRI Revolution

- The introduction of the SSRIs revolutionized the treatment of depression and other psychiatric disorders, as these medications had a wider therapeutic index, and were more well tolerated with less side effects.

Mechanism of Action

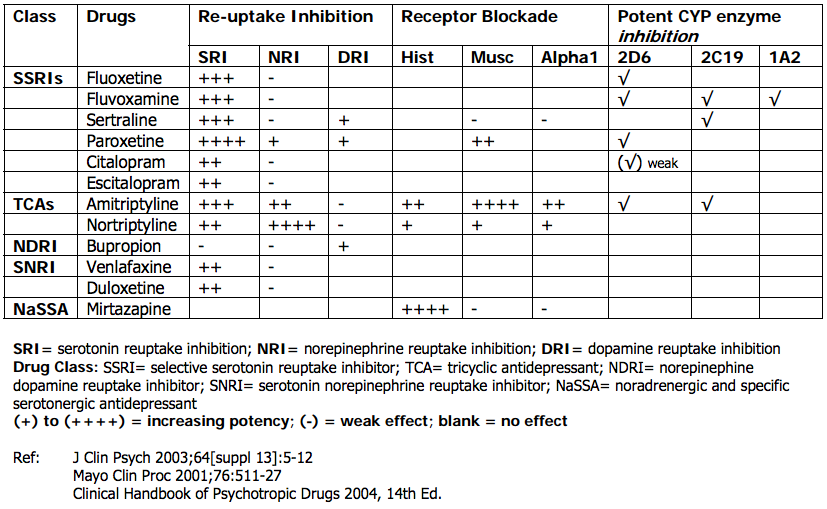

- Given the wide range of classes of antidepressants, each of them have their own specific mechanism of action. The key mechanism of action of most modern antidepressants is some modulation of serotonin reuptake, while others have more dopaminergic/noradrenergic effects (e.g - bupropion).

- Older antidepressants such as TCAs and MAOIs also work by other mechanisms. For example, MAOIs work by inhibiting monoamine oxidase, which slows the breakdown of norepinephrine, serotonin and dopamine in the brain.

Monoamine Hypothesis

- Despite many decades of research, there is no single proven theory that supports the monoamine hypothesis.

- The monoamine hypothesis is too reductionistic and simplistic to explain complex a phenomenon such as depression.

- Although the specific mechanism of how antidepressants improve mood, ahedonia, and neurovegetative symptoms is not well understood, the use of these medications remains indicated for treatment of psychiatric disorders.

- Drawing parallels from other areas of medicine, general anesthesia has been used for over 160 years, yet there is still no formal understanding of the exact mechanism of how it works and why patients fall asleep.[8][9] There are also rare, but significant risks with use, such as memory impairment and death.[10] Despite this, general anesthesia remains in widespread use because of its benefits.

Antidepressant Classes

- There are a many different classes of antidepressants. The landmark antidepressant trial, STAR*D, has shown that no one class of antidepressant is more effective than another.[11]

- The data from the this landmark is not without its criticisms, but it is the largest scale study of psychiatric medications that is available in the literature.[12]

- In general, most clinicians will pick a medication based on the patient's reported symptoms, comorbid diagnoses, tolerability to medications, previous response, drug–drug interactions, and the patient's own preference.[13]

- The cost of the medication should also be considered for patients from a lower socioeconomic background.

- Other classes of antidepressants can be tailored according patient symptom profiles, such as using mirtazapine (which is sedating and an appetite stimulant) for patients who report poor appetite and sleep. Conversely, patients who have anxiety or anxious symptoms should avoid noradrenergic antidepressants (e.g. - NDRIs such as bupropion). Paroxetine is generally not recommended as a first-line medication as it is very potent, and has the most severe withdrawal symptoms if the patient discontinues it abruptly.

SSRIs, SNRIs, NDRIs, MAOIs, TCAs... What Do I Use?!

In terms of safety profile and prescribing practices, most clinicians now prescribe SSRIs, SNRIs, and other newer agents. Newer antidepressants generally have a better tolerability and safety profile. However, several decades ago, TCAs and MAOis were the predominant antidepressants. These medications remain effective for the treatment of depression, but are no longer in widespread use due to the narrow therapeutic index for TCAs, and the diet-restriction that is required with MAOi use (to prevent hypertensive crises). Experienced clinicians will be familiar using all classes of antidepressants and tailoring it to specific patient needs. The best antidepressant is the one that the patient actually uses.

Common Antidepressant Choices

| Escitalopram | Low side effect profile, good for treatment with comorbid medical illness.[14] Commonly prescribed in primary care settings. Unfortunately it has a narrow dose range (maximum 20mg), due to increased risk of QTc prolongation at higher doses. This means you can only increase the dose so much before needing to switch to another antidepressant if there is no response. |

|---|---|

| Sertraline | Good for patients with comorbid psychiatric diagnoses. Indicated as a first-line medication for not just depression, but also generalized anxiety, obsessive compulsive disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, social anxiety disorder and other disorder. Sometimes felt by clinicians to be more sedating than other SSRIs, but the research evidence does not necessarily demonstrate this.[15] Sertraline has a higher incidence of GI side effects which can be mitigated by taking it with food, and with HS dosing, but this can be a reason for discontinuation. |

| Fluoxetine | Another good first-line choice and very similar to sertraline, with less GI side effects. It has the added benefit of also treating any comorbid eating disorders. It also has a long half-life, which means very little chance of withdrawal symptoms even if it is discontinued abruptly. |

Neurotransmitters and Neuroreceptors

See main article: Introduction to Neurotransmitters and Receptors

- From a neurotransmitter and physiology point of view, antidepressants with serotonin activity may help more with cognitive symptoms such as rumination, where as norephinephrine reuptake affects more of the behavioural symptoms (anhedonia, low mood). TCAs have alpha blockade, which lead to postural hypotension, and dizziness. Mirtazapine has high histamine blockade which leads to drowsiness, weight gain, which sometimes can be used for the benefit of a patient's poor appetite and sleep.

Treatment

Education

- It is important to educate patients about how medications work, and how side effects occur. It is important to remind patients that side effects start early in treatment, and the benefits of the medications come later (“Think of this as an investment in the future!”).

- There is huge variability in the side effect profiles that patients experience, despite our understandings of the psychopharmacology of these medications. What might work for one patient may not work for another.

Length of Treatment

- In the treatment of mood and anxiety disorders, some may experience benefits in the first six weeks of a treatment strategy, but full benefits may not be realized until 10 or 12 weeks have passed. During this time, doctors should work with their patients to adjust dosages so as to find an optimal level, and avoid stopping treatment prematurely.

- For a first episode of depression, the general recommended treatment timeline is 1 year. For a second episode, 2 years of treatment is recommended. For any third and subsequent episodes, lifetime treatment is recommended, as the risk of relapse is close to 100% off treatment.[16]

Monitoring

See also: Measurement-Based Care (MBC)

- Patients should be carefully monitored every 1 to 2 weeks when first starting medications, as this is the period of greatest risk, including side effects. Treatment should be monitored with the routine use of validated outcome scales.

When Not to Treat

Switching/Tapering

See also: Tapering/Switching Antidepressants

Withdrawal and Discontinuation

- When a patient stops an antidepressant abruptly, antidepressant withdrawal (discontinuation syndrome) is a very clinically important phenomenon to monitor for.

- Different antidepressants will have different discontinuation side effects.[17]

- Psychiatric symptoms of discontinuation such as anxiety and agitation, crying spells, or irritability are also sometimes misdiagnosed as a depressive relapse. Antidepressants should thus be tapered slowly and on a schedule.

Side Effects and Adverse Events

Common

- Common side effects include nausea, headaches, and gastrointestinal issues including nausea or diarrhea.

- Most of these side effects will self-resolve 1 to 2 weeks into treatment. Some may experience sexual dysfunction or loss of libido and it is important to screen and monitor for this in patients.

Sexual Dysfunction

See main article: Antidepressant-induced Sexual Dysfunction

Sweating

- Excessive sweating can be common in patients on SSRIs and SNRIs.[18]

- The mechanism not understood but likely related to 5-HT receptors or NE reuptake inhibition

- Severe cases have been reported (especially in summer months)

- Benztropine, clonidine or terazosin may be helpful, or switching to another SSRI may be helpful (sweating may be most likely to occur with paroxetine and least likely with escitalopram)

Older Adults

In the elderly, falls can also be common with the use of SNRIs, TCAs, but less commonly in SSRIs.[19]

Hyponatremia

See also: Hyponatremia

- The incidence of hyponatremia caused by SSRIs varies widely, from 0.5% to 32%. In the majority of cases, hyponatremia occurs within the first few weeks of the onset of therapy. The hyponatremia typically resolves 2 weeks after discontinuation of the SSRI.[20]

- Routine monitoring of sodium levels is important in elderly.

Sleep

- Almost all antidepressants decrease sleep efficiency, increase REM latency, suppress REM, delay REM onset, increase number of awakenings, worsen PLMS and RLS, can worsen parasomnias, and increase Stage 1 sleep.[21]

- The exceptions to this are trazodone and bupropion. SSRIs can have idiosyncratic effects on sleep, and they may cause insomnia or agitation in any individual patient.

Controversy

Placebo Effect?

See also: The Placebo Effect

See also:

- In recent years, a popular and controversial theory has emerged through the media and the literature suggesting that modern antidepressants (SSRIs and beyond), do not exert any actual antidepressant effect (but is instead all driven by a placebo response).[24][25] Decades of research into the effects and mechanisms of antidepressants suggests that there are significant physiological mechanisms at work.[26]

- Prior to the development of SSRIs, tricyclic antidepressants and monoamine oxidase inhibitors were the dominant classes of antidepressants, and the efficacy of these medications were very well documented at the time.[27] The decades of research, latest large scale meta-analyses, and clinical evidence pushes against the theory that antidepressants are a pure placebo[28][29][30] The largest known study on antidepressant efficacy to date supports the efficacy and use for the acute treatment of adults with major depressive disorder (but this meta-analysis had its own limitations[31]).[32] More recent re-evaluation of placebo studies have shown that the placebo response rate has in fact has not increased over time.[33]

- Despite the evidence of efficacy in short-term use, it is important to recognize there is a definite and strong placebo response to antidepressants. Most studies show a placebo response of anywhere from 30-40% in major depressive disorder.[34][35] However, it should also be noted this phenomenon is not just limited to psychiatry. The placebo effect is pervasive and apparently increasing throughout all areas of medicine. This includes sham surgeries in benign prostatic hyperplasia,[36] sham percutaneous coronary intervention in stable angina,[37] arthroscopy for osteoarthritis,[38] antiepileptic treatment of migraines,[39] bronchodilators for asthma,[40] and many others.[41][42]

- Just like with antidepressants, it does not mean that these treatments do not work, but that medicine is both an art and a science, and that every treatment decision requires clinical judgement and judicious use. The placebo response is poorly understood, and likely involves a complex interaction between neurobiologic mechanisms and the therapeutic doctor-patient interaction.[43]

Aggression

- The role of antidepressants, specifically SSRIs, in causing aggression/violence has been debated since their introduction in the 1980s, especially in the popular media.[44] Studying aggression is complicated, as human behaviour is complex and multifactorial. There are multiple confounding factors and variables that research cannot necessarily capture. A controversial paper was published in 2016 by Bielefeldt et al suggested that SSRIs doubled the risk of suicide/violence.[45] However, the paper was a meta-analysis that reviewed original papers. Importantly, there were no actual reported violent events or suicides, but adverse events (such as increased anxiety) were extrapolated to include the possibility that it could lead to violence/suicides.[46]

- A comprehensive review of the literature so far reveals limited evidence to support the hypothesis that modern antidepressants increase suicidality or aggression in adults.[48]

Suicide

See also:

- Although there is no evidence of increased suicidal behaviours in adults, it is more clear that antidepressant use in the pediatric and young adult (age <24 years) population can result in increased agitation and suicidal behaviours.

- In 2003, the FDA issued a black-box warning because a meta-analysis found a 1.5 to 2-fold increase in increased suicidal thoughts/behaviours (although there was no increased incidence of suicide deaths).

- Similarly, observational studies have found an increased risk for suicidal acts including suicide attempts. These findings are opposite of what is seen in other age groups (e.g. - geriatric and older adults) where SSRI use actually shows a decrease in suicidality.[49]

- Thus, it is important to be vigilant about the use of antidepressants in young adults and the pediatric population and monitor for suicidal behaviours or thoughts.

- This is why antidepressants should not used as a first-line treatment in children for mild-moderate depression, and psychosocial interventions (e.g. - cognitive behavioural therapy) should always be used first.

- In Canada, antidepressants have not been approved by Health Canada for individuals younger than age 18, so its use is off-label.

- In the United States, fluoxetine is the only antidepressant approved by the FDA for preadolescents (8 years and older) and escitalopram is also approved for children 12 years and older.

- It is important to have a clear risk-benefit discussion between clinicians and their patients under these circumstances

Study 329: A Story of Pharmaceutical Influence

A re-analysis in 2015 of Study 329 on the efficacy and safety of paroxetine for children and adolescents showed that paroxetine was neither safe nor efficacious.[50] In fact, there was significant harm exposed to children, including increased suicidal ideation and behaviour. This case is a reminder to clinicians of the large role thatpharmaceutical influence still has on healthcare.Research Supporting Antidepressants in Reducing Suicide Risk

Fetal Effects

See also: Obstetric and Fetal Pharmacology

- Recent controversy has come up regarding concerns about the incidence of mental illness (autism, mood disorders, somatoform disorders, and behavioural disorders) in offspring of mothers taking SSRIs.

- Although animal studies of the neurobehavioral outcomes of fetal antidepressant exposure suggest mechanisms for such effects, most human studies indicate that maternal psychiatric illness account for much (but not all) of this risk.

- The fraction of cases attributable to antidepressant use (0.5%) is substantially lower than what would be attributable to parental psychiatric illness.

- Antidepressant use late in pregnancy and has been associated with a risk of persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn.[53]

Mortality

- Ongoing research and clinicians have brought on concerns about antidepressants being generally harmful, because they may disrupt ancient neurotransmitters such as serotonin, which plays a role in not just neurotransmission, but also other important bodily functions.[54] There are concerns that alterations to these ancient processes could potentially increase mortality.

- Therefore, questions have been raised not necessarily about their short-term use, but the long-term health effects.[55]

- It is also important to recognize that antidepressants also have anticlotting properties that can be efficacious in treating cardiovascular disease and stroke. Various studies have in fact reinforced the importance of early treatment with antidepressants in post-stroke as it improves recovery.[56]

Like All Things in Medicine, There Are Risks and Benefits!

The role of SSRIs in mortality should continue to be investigated. Like all medications and medical procedures, there are risks and benefits that must be considered. A patient has a possibility of dying during an operation from not just the surgery itself, but also with general anesthetics. The current research evidence also suggests that for mild-moderate depression, medication and psychotherapy leads to the same rate of improvement. Therefore, it may make sense that the role of antidepressants should focus more on patients who are experiencing severe depression. Like with any medication, patients should be counselled on the risks and benefits of taking an antidepressant. It is undeniable that for many patients, short-term, judicious use of antidepressants leads to significant clinical improvements. What is more needed is the integration of psychotherapies and other non-pharmacological options to sustain recovery.Resources

For Patients

Articles

Research

References

1)

Discover Magazine: The Psychic Energizer!: The Serendipitous Discovery of the First Antidepressant

2)

Steinberg, H., & Himmerich, H. (2012). Roland Kuhn—100th Birthday of an Innovator of Clinical Psychopharmacology. Psychopharmacology bulletin, 45(1), 48.

3)

Brown, W. A., & Rosdolsky, M. (2015). The clinical discovery of imipramine. American Journal of Psychiatry, 172(5), 426-429.

4)

López-Muñoz, F., & Alamo, C. (2009). Monoaminergic neurotransmission: the history of the discovery of antidepressants from 1950s until today. Current pharmaceutical design, 15(14), 1563-1586.

5)

INHN: Trudo Lemmens: Promoting pharmaceutical treatment in a context of knowledge deficit: the case by the CINP Task Force in Depression

6)

Mojtabai, R. (2013). Clinician-identified depression in community settings: concordance with structured-interview diagnoses. Psychotherapy and psychosomatics, 82(3), 161-169.

7)

Tan, M. (2016). Overdiagnosis in Psychiatry: How Modern Psychiatry Lost Its Way While Creating a Diagnosis for Almost All of Life's Misfortunes.

8)

Lugli, A. K., Yost, C. S., & Kindler, C. H. (2009). Anaesthetic mechanisms: update on the challenge of unravelling the mystery of anaesthesia. European journal of anaesthesiology, 26(10), 807.

10)

Brown, E. N., Lydic, R., & Schiff, N. D. (2010). General anesthesia, sleep, and coma. New England Journal of Medicine, 363(27), 2638-2650.

11)

Warden, D., Rush, A. J., Trivedi, M. H., Fava, M., & Wisniewski, S. R. (2007). The STAR* D Project results: a comprehensive review of findings. Current psychiatry reports, 9(6), 449-459.

12)

Pigott, H. E. (2015). The STAR* D trial: it is time to reexamine the clinical beliefs that guide the treatment of major depression. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 60(1), 9-13.

13)

Lam, R. W., Kennedy, S. H., Grigoriadis, S., McIntyre, R. S., Milev, R., Ramasubbu, R., ... & Ravindran, A. V. (2009). Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) Clinical guidelines for the management of major depressive disorder in adults.: III. Pharmacotherapy. Journal of affective disorders, 117, S26-S43.

14)

Sanchez, C., Reines, E. H., & Montgomery, S. A. (2014). A comparative review of escitalopram, paroxetine, and sertraline: are they all alike?. International clinical psychopharmacology, 29(4), 185.

15)

Warrington, S. J. (1991). Clinical implications of the pharmacology of sertraline. International clinical psychopharmacology, 6, 11-22.

16)

Shelton, R. C. (2001). Steps following attainment of remission: discontinuation of antidepressant therapy. Primary care companion to the Journal of clinical psychiatry, 3(4), 168.

17)

Shelton, R. C. (2001). Steps following attainment of remission: discontinuation of antidepressant therapy. Primary care companion to the Journal of clinical psychiatry, 3(4), 168.

18)

Options for treating antidepressant-induced sweating. Current Psychiatry. 2013 January;12(1):51-51. Jonathan R. Scarff, MD.

19)

Darowski, A., Chambers, S. A. C., & Chambers, D. J. (2009). Antidepressants and falls in the elderly. Drugs & aging, 26(5), 381-394.

20)

Jacob, S., & Spinier, S. A. (2006). Hyponatremia associated with selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors in older adults. Annals of Pharmacotherapy, 40(9), 1618-1622.

21)

Wichniak, A., Wierzbicka, A., Walęcka, M., & Jernajczyk, W. (2017). Effects of antidepressants on sleep. Current psychiatry reports, 19(9), 63.

22)

Armitage, R., Emslie, G., & Rintelmann, J. (1997). The effect of fluoxetine on sleep EEG in childhood depression: a preliminary report. Neuropsychopharmacology, 17(4), 241-245.

25)

Ioannidis, J. P. (2008). Effectiveness of antidepressants: an evidence myth constructed from a thousand randomized trials?. Philosophy, Ethics, and Humanities in Medicine, 3(1), 14.

26)

Feighner, J. P. (1999). Mechanism of action of antidepressant medications. In Assessing Antidepressant Efficacy: A Reexamination., Jan, 1998, Phoenix, AZ, US. Physicians Postgraduate Press.

27)

Fiedorowicz, J. G., & Swartz, K. L. (2004). The role of monoamine oxidase inhibitors in current psychiatric practice. Journal of psychiatric practice, 10(4), 239.

28)

Hieronymus F, et al. Efficacy of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in the absence of side effects: a mega-analysis of citalopram and paroxetine in adult depression (2017)

29)

Hieronymus, F., Emilsson, J. F., Nilsson, S., & Eriksson, E. (2016). Consistent superiority of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors over placebo in reducing depressed mood in patients with major depression. Molecular psychiatry, 21(4), 523-530.

30)

Parker, G., Roy, K., Wilhelm, K., & Mitchell, P. (2001). Assessing the comparative effectiveness of antidepressant therapies: a prospective clinical practice study. The Journal of clinical psychiatry, 62(2), 117-125.

31)

Munkholm, K., Paludan-Müller, A. S., & Boesen, K. (2019). Considering the methodological limitations in the evidence base of antidepressants for depression: a reanalysis of a network meta-analysis. BMJ open, 9(6), e024886.

32)

Cipriani, A., Furukawa, T. A., Salanti, G., Chaimani, A., Atkinson, L. Z., Ogawa, Y., ... & Egger, M. (2018). Comparative efficacy and acceptability of 21 antidepressant drugs for the acute treatment of adults with major depressive disorder: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. The Lancet.

33)

Furukawa, T. A., Cipriani, A., Leucht, S., Atkinson, L. Z., Ogawa, Y., Takeshima, N., ... & Salanti, G. (2018). Is placebo response in antidepressant trials rising or not? A reanalysis of datasets to conclude this long-lasting controversy. Evidence-based mental health, 21(1), 1-3.

34)

Sonawalla, S. B., & Rosenbaum, J. F. (2002). Placebo response in depression. Dialogues in clinical neuroscience, 4(1), 105.

35)

Khan, A., & Brown, W. A. (2015). Antidepressants versus placebo in major depression: an overview. World Psychiatry, 14(3), 294-300.

36)

Welliver, C., Kottwitz, M., Feustel, P., & McVary, K. (2015). Clinically and statistically significant changes seen in sham surgery arms of randomized, controlled benign prostatic hyperplasia surgery trials. The Journal of urology, 194(6), 1682-1687.

37)

Al-Lamee, R., Thompson, D., Dehbi, H. M., Sen, S., Tang, K., Davies, J., ... & Nijjer, S. S. (2018). Percutaneous coronary intervention in stable angina (ORBITA): a double-blind, randomised controlled trial. The Lancet, 391(10115), 31-40.

38)

Moseley, J. B., O'malley, K., Petersen, N. J., Menke, T. J., Brody, B. A., Kuykendall, D. H., ... & Wray, N. P. (2002). A controlled trial of arthroscopic surgery for osteoarthritis of the knee. New England Journal of Medicine, 347(2), 81-88.

39)

Khan, A., Mar, K. F., Schilling, J., & Brown, W. A. (2017). Magnitude and pattern of placebo response in clinical trials of antiepileptic medications: Data from the Food and Drug Administration 1996–2016. Contemporary Clinical Trials.

40)

Wechsler, M. E., Kelley, J. M., Boyd, I. O., Dutile, S., Marigowda, G., Kirsch, I., ... & Kaptchuk, T. J. (2011). Active albuterol or placebo, sham acupuncture, or no intervention in asthma. New England Journal of Medicine, 365(2), 119-126.

41)

Kaptchuk, T. J., & Miller, F. G. (2015). Placebo effects in medicine. New England Journal of Medicine, 373(1), 8-9.

43)

Paterson, C., & Dieppe, P. (2005). Characteristic and incidental (placebo) effects in complex interventions such as acupuncture. BMJ: British Medical Journal, 330(7501), 1202.

45)

Bielefeldt, A. Ø., Danborg, P. B., & Gøtzsche, P. C. (2016). Precursors to suicidality and violence on antidepressants: systematic review of trials in adult healthy volunteers. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 109(10), 381-392.

47)

Lucire, Y., & Crotty, C. (2011). Antidepressant-induced akathisia-related homicides associated with diminishing mutations in metabolizing genes of the CYP450 family. Pharmacogenomics and personalized medicine, 4, 65.

48)

Sharma, T., Guski, L. S., Freund, N., & Gøtzsche, P. C. (2016). Suicidality and aggression during antidepressant treatment: systematic review and meta-analyses based on clinical study reports. bmj, 352, i65.

49)

Gibbons, R. D., Brown, C. H., Hur, K., Davis, J. M., & Mann, J. J. (2012). Suicidal thoughts and behavior with antidepressant treatment: reanalysis of the randomized placebo-controlled studies of fluoxetine and venlafaxine. Archives of general psychiatry, 69(6), 580-587.

50)

Le Noury, J., Nardo, J. M., Healy, D., Jureidini, J., Raven, M., Tufanaru, C., & Abi-Jaoude, E. (2015). Restoring Study 329: efficacy and harms of paroxetine and imipramine in treatment of major depression in adolescence. Bmj, 351, h4320.

51)

Rapid Response: Antidepressant use during pregnancy and psychiatric disorders in offspring: Danish nationwide register based cohort study

52)

NEJM Journal Watch: Antidepressant Use During Pregnancy May Raise Risk for Psychiatric Illness in Offspring

53)

Huybrechts, K. F., Bateman, B. T., Palmsten, K., Desai, R. J., Patorno, E., Gopalakrishnan, C., ... & Hernandez-Diaz, S. (2015). Antidepressant use late in pregnancy and risk of persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn. Jama, 313(21), 2142-2151.

54)

Andrews, P. W., Thomson Jr, J. A., Amstadter, A., & Neale, M. C. (2012). Primum non nocere: an evolutionary analysis of whether antidepressants do more harm than good. Frontiers in psychology, 3.